Wheat procurement by government agencies is set to dip to a 15-year low in the current marketing season, from an all-time high scaled last year.

The 18.5 million tonnes (mt) likely procurement this time — farmers mostly sell from April to mid-May, although government wheat purchases technically extends until June and the marketing season until the following March — will be the lowest since the 11.1 mt bought in 2007-08.

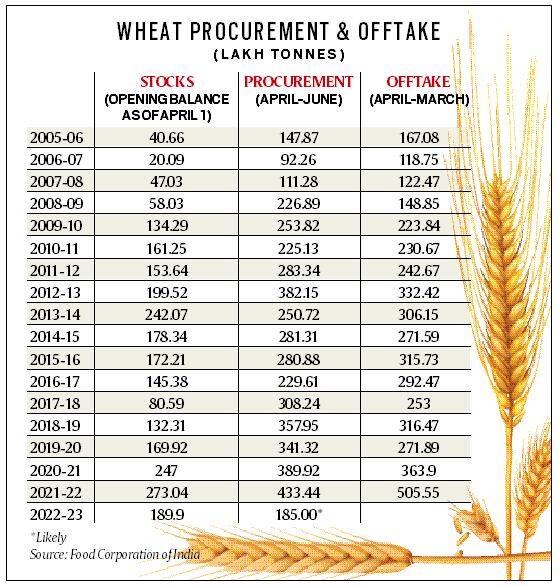

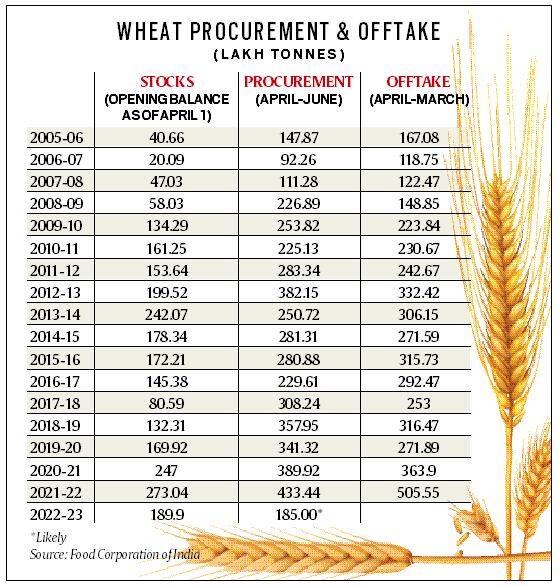

Moreover, this would be the first time that wheat procured from the new crop (18.5 mt) is less than the public stocks at the start of the marketing season (19 mt). As the table shows, fresh procurement has always exceeded the opening balance stocks. It was so even during the previous two low procurement years of 2006-07 and 2007-08.

This year would be an exception and in sharp contrast to 2020-21, which had unprecedented levels of both opening stocks (27.3 mt) and procurement (43.3 mt).

Why it has fallen

There are two main reasons for procurement plunging to a 15-year-low this time.

The first is export demand.

In 2021-22, India exported a record 7.8 mt of wheat. Supply disruptions from the Russia-Ukraine war – the two countries account for over 28% of global wheat exports – have led to skyrocketing prices and a further increase in demand for Indian grain. On Friday, wheat futures prices at the Chicago Board of Trade exchange closed at $407.30 per tonne, as against $276.77 a year ago. With Indian wheat getting exported at about $350 or Rs 27,000 per tonne free-on-board (i.e. at the point of shipping), farmers are realising well above the minimum support price (MSP) of Rs 20,150/tonne at which government is procuring. This is even after deducting various costs – from bagging and loading at the purchase point, to transport and handling at the port. These would add up to Rs 4,500-6,000 per tonne, depending on the distance from the wholesale mandi to the port.

The second reason is lower production.

In mid-February, the Union Agriculture Ministry estimated the size of India’s 2021-22 crop (marketed during 2022-23) at 111.32 mt, surpassing even the previous year’s high of 109.59 mt. But the sudden spike in temperatures from the second half of March — when the crop was in grain-filling stage, with the kernels still accumulating starch, protein and other dry matter — has taken a toll on yields. In most wheat-growing areas — barring Madhya Pradesh, where the crop is harvest-ready by mid-March — farmers have reported a 15-20% decline in per-acre yields.

A smaller crop, in combination with export demand, has resulted in open market prices of wheat crossing the MSP in many parts of India. The shorter the distance to the ports, the higher the premium that exporter/traders have paid over the MSP. Even in Punjab and Haryana — where the state governments charge up to 6% market levies, compared to 0.5-1.6% in MP, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan — flour millers have paid farmers Rs 50-100 above the MSP of Rs 20,150 per tonne. Traders and millers aren’t the only ones stocking up in anticipation of prices going up further. Many farmers, especially the more entrepreneurial/better-off sections among them, are also holding back their crop. Such “hoarding” by farmers was seen in the recent past in soyabean and cotton, too, again driven by soaring international prices.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

The end-result of a heatwave-affected crop and open market prices rising closer to export parity levels has been that procurement by government agencies has plummeted to 9.6 mt in Punjab (from 13.2 mt last year), and even more in MP (12.8 mt to 4 mt), Haryana (8.5 mt to 4.1 mt) and other states (8.8 mt to not more than 0.8 mt).

Impact on availability

With opening stocks of 19 mt and expected procurement of 18.5 mt, government agencies would have 37.5 mt of wheat available for 2022-23. Not all this, however, can be sold, as a minimum operational stock-cum-strategic reserve has to be maintained. The normative buffer or closing stock requirement for March 31 is 7.5 mt. Providing for that will leave 30 mt available for sale from government godowns this fiscal.

That quantity should suffice for the public distribution system, midday meals and other regular welfare schemes, whose annual wheat requirement is around 26 mt. But the last two years have also witnessed substantial offtake under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana scheme (10.3 mt in 2020-21 and 19.9 mt in 2021-22) and open market sales to flour mills (2.5 mt and 7.1 mt, respectively). There’s clearly not enough wheat for these, which explains the Centre’s recent decision to slash allocation under the PMGKAY from 10.9 mt to 5.4 mt for April-September 2022. Meeting even this requirement may not be easy, leave alone supplying to millers and other bulk consumers to moderate open market prices during the lean months after October.

Simply put, one can expect wheat prices to firm up and a rerun of what happened in 2006-07 and 2007-08. That period, too, saw a worldwide agri-commodity price boom and production shortfalls, causing reduced procurement and depletion of stocks.

However, the relatively tight supplies in wheat this time is compensated for by the comfortable public stocks of rice. At over 55 mt as on April 1, these were more than four times the required buffer of 13.6 mt. And a good monsoon should further augment availability from the ensuing kharif crop and tide over the shortages in wheat.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

.