Earthquake in Haiti, volcanic eruption in Indonesia, Hurricane Ida in the US, typhoon Rai in the Philippines, and floods in Australia, Belgium, China, Germany, India, and Nepal – over the last year, these have illustrated the intensity and the frequency of natural disasters all over the world. The economic costs of natural disasters have risen dramatically over the last decades, reaching $190 billion in 2020, against (2020) $1.3 billion in 1970 (Sigma 2021). Natural disasters impacted insurers, with $89 billion of insured losses in 2020. For the large uninsured part, they impacted households, businesses and banks (Hosono and Miyakawa 2014).

Figure 1 New Orleans

Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/new-orleans-louisiana-81669/

Besides the escalating climate crisis, this rise in the economic costs of disasters is largely explained by the growing number of people and businesses in exposed areas and the value of their assets (Hallegatte 2012). Many areas that are exposed to catastrophic risks are indeed inhabited and used for economic activities. In China, as early as 2004, 50% of the population was living in the 8% of land area in the midstream and downstream parts of the country’s seven major flood-prone rivers. They contribute over two-thirds of the country’s total agricultural and industrial product value. In Florida in 2012, 80% (or $2.9 trillion) of insured assets were located near the coasts – the highest risk areas in the state. Globally, the world’s coastal areas host a large and growing population in many of the world’s largest cities.

This growing urbanisation in exposed areas is partly due to amenities linked to risk – riversides are attractive. Perception biases play their roles – people underestimate risk, are forgetful of past events or are unaware of the ongoing climate change, not to mention climate scepticism. Local public authorities may also fail to communicate about actual risks for fear that the area’s attractiveness or real-estate values would be negatively affected (Burby 2006).

Economic also incentives matter. Urbanisation is favoured when households who settle in the exposed areas do not bear the full cost of the risk they take. Our focus in this column and in our 2019 paper is on this type of free-riding (Grislain-Letrémy and Villeneuve 2019). We limit our scope to the non-life losses from these disasters.

The solutions to control urbanisation in exposed areas combine land-use and insurance policies:

- Land-use policies lead sometimes to strong actions. For example, since the Great Flood of 1993 in the US, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has acquired nearly 4,500 flood-prone homes in the state of Missouri; entire towns, such as Valmeyer, Illinois, have also moved from the floodplain to higher ground.

- Insurance policies can also limit free-riding by making households and businesses in exposed areas pay for the risk they take. For example, the earthquake insurance premiums in Japan or the flood insurance premiums in the US increase with the risk exposure. Even in these cases, the premium increase is regulated.

To show how land-use regulations and insurance premiums shape risk exposure, we develop an urban model of a linear city with a significant risk gradient, where we endogenise the land rents, insurance premiums, and location choices.

Risk capitalisation in property values and the impact of insurance prices

Risks impose a servitude to real estate. Asset values should reflect differences in risk. Thus, a property in a flood zone or in a region subject to earthquakes is depreciated by the real estate market. If insurance is available, the negative capitalisation originates from insurance premiums. Empirical studies based on the hedonic price method confirm that real estate markets value the capitalised flow of natural catastrophe insurance premiums (Bin et al. 2008, MacDonald et al. 1990, Harrison et al. 2001). Experience shows that real estate prices react more to revisions in insurance premiums than to other risk revelations (Skantz and Strickland 1987).

Insurance is often location-blind. Location-blind premiums are of two types. The first is implicit universal insurance, namely, assistance expected from the state in case of disaster. In Australia, Canada, China, and in many European countries such as Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Poland, flood compensation relies on state-funded assistance schemes with a de facto compulsory and uniform contribution to coverage (private insurance being either non-existent or purchased by few households or firms) (Ahvenharju et al. 2011, Consorcio de Compensación de Seguros 2008, Maccaferri et al. 2012). Even in the US, flood insurance is purchased by a minority of households, partly because of the expectation of federal assistance (Dixon et al. 2006, Kunreuther and Pauly 2005) and the non-requirement of flood insurance for cash buyers (Palm and Bolsen 2022). The second type of location-blind premium is legally non-discriminatory insurance pricing, such as exists in Denmark, France, Spain, and Switzerland. This second type is often the modernisation of the first (Dumas et al. 2005).

In most countries, inefficient pricing (of either of the two types) is accompanied by building prohibition. For example, in France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, and Switzerland, there is binding legislation restricting or prohibiting the development of flood-prone areas (Santato 2013).

Under location-blind insurance – assuming that the insurance is complete – all properties become artificially equivalent, leading to overuse of the riskiest places. In practice, this negative effect is somewhat moderated by the fact that insurance is in fact incomplete.

A typical result of economic analysis is that the insurance premiums (price incentives) are, in principle, as efficient as zoning (quantity regulation). Equivalence goes even further. Prices and zoning are substitutes at any scale. Zoning can increase degrees of efficiency in a territory uniformly treated by insurance; insurance-tariff differentiations can make up for the imperfection of zoning.

Examining the power of second-best solutions: Red-zone policies

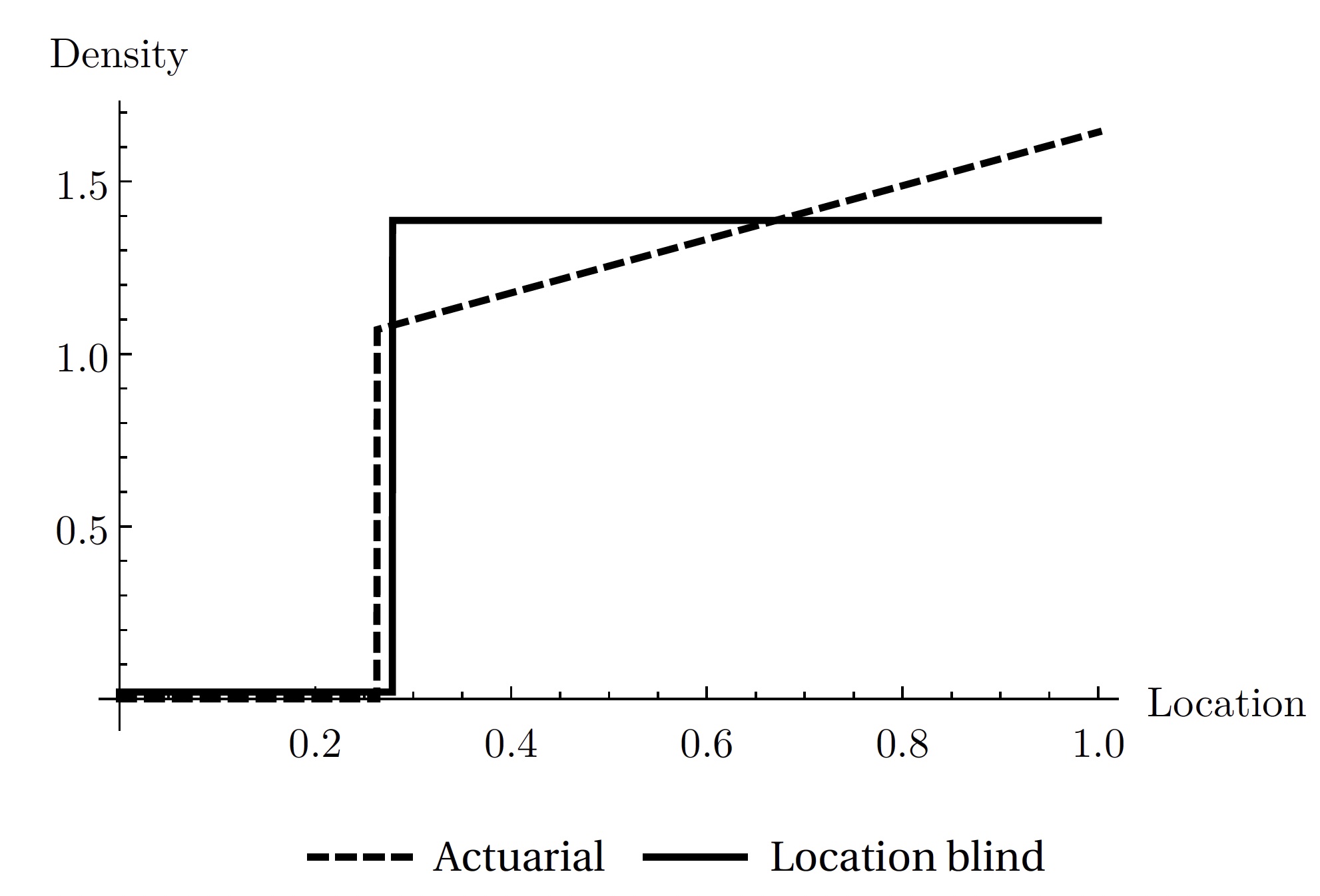

We thoroughly investigate the most commonly used two-zone policy. In the red zone, dwellings are prohibited; in the building zone, authorised density and insurance premiums are location-blind.

Figure 2 Red zone

Overall, potential losses increase with the surface used and with the number of inhabitants. If surface mostly matters, then forbidding the worst places is efficient. In contrast, if density mostly matters, then density restrictions must decrease with basic risk. Yet, we illustrate with simulations that the red-zone policy is relatively efficient.

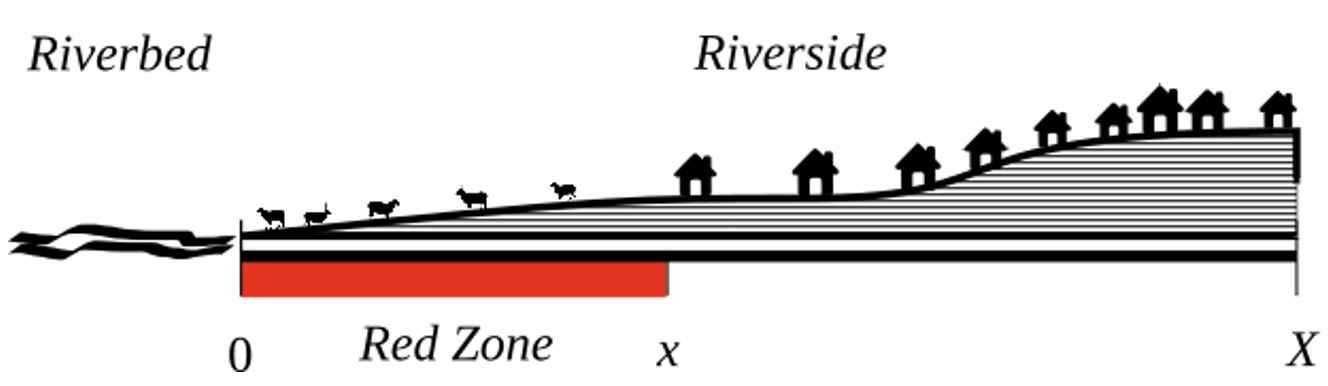

Figure 3 shows a simulation of the equilibrium densities under location-blind insurance with the optimal red zone (solid line) and a simulation of the first-best equilibrium with actuarially fair pricing (dashed line). Location-blind premiums lead to uniform use of the whole authorised space; actuarially fair insurance provides smooth incentives for households to concentrate in less risky areas. Under actuarially fair insurance, the riskiest areas are spontaneously deserted. This zone is smaller than the optimal red zone: actuarially fair premiums enable better and more extensive land occupation.

Figure 3 Equilibriums: Actuarially fair premiums versus location-blind premiums and optimal red zone

Notes: Simulation of the equilibrium densities under location-blind insurance with the optimal red zone (solid line) and a simulation of the first-best equilibrium with actuarially fair pricing (dashed line).

In addition to the extreme cases of actuarially fair and location-blind insurance, we simulate the equilibrium when insurance is partially subsidised. These simulations confirm that red-zone policies are more useful as the subsidy is high, which can be seen as substitutability between the financial incentives and the physical constraints. These simulations also provide insights about substitutability when there are amenities or finely tuned building codes.

What happens when risk changes?

Updating the zoning as risk changes is crucial. We determine the impact of climate change and demographic pressure on optimal red zones. Currently, the increasing cost of natural disasters is largely explained by the growing urbanisation in exposed areas. The European Parliament and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change show how climate change will increase the intensity and the frequency of natural disasters. Global flood damage for large coastal cities will increase eightfold between 2005 and 2050, with projections based only on increasing population and property value. Once climate change and subsidence are added, global flood damage for large coastal cities could increase 19-fold and cost $1 trillion a year if prevention is not upgraded.

The impact of climate change and demographic evolution on the design of optimal red zones can be counterintuitive. We propose a thorough description of the competing effects in the general case. As expected, extending the red zone as disaster frequency or seriousness increases contains the final incidence. In contrast, a population increase raises the risk but increases the demand for land at the same time. The net impact of demographic pressure can be a reduction in the red zone when expected damages per head are small (and an extension in the red zone when expected damages are big) compared to expected damages per surface unit.

Difficult management of the existing

How should we deal with the people and assets already located in highly exposed areas? The logic of incitement has a pitfall here: it is tempting to exempt existing dwellings from unfavourable revisions of risk exposure. ‘Grandfather rights’, widely taken up, lead to repeated losses. There should be instead a clear risk update and a shift in insurance compensation from a pay-to-rebuild to a pay-to-move principle.

References

Ahvenharju, S, Y Gilbert, J Illman, J Lunabba and I Vehvilainen (2011), “The role of the insurance industry in environmental policy in the Nordic countries”, Nordic Innovation Publication (2).

Bin, O, J B Kruse and C E Landry (2008), “Flood hazards, insurance rates, and amenities: Evidence from the coastal housing market”, Journal of Risk and Insurance 75(1): 63–82.

Burby, R J (2006), “Hurricane Katrina and the paradoxes of government disaster policy: Bringing about wise governmental decisions for hazardous areas”, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 604(1): 171–91.

Consorcio de Compensación de Seguros (2008), Natural catastrophes insurance cover: A diversity of systems.

Dumas, P, A Chavarot, H Legrand, A Macaire, C Dimitrov, X Martin and C Queffelec. (2005), “Rapport particulier sur la prévention des risques naturels et la responsabilisation des acteurs”, Mission d‘Enquête sur le Régime d‘Indemnisation des Victimes de Catastrophes Naturelles, French Treasury General Inspection, French Environment General Inspection and French General Council of Civil Engineering.

Grislain-Letrémy, C, and B Villeneuve (2019), “Natural disasters, land use, and insurance”, Geneva Risk and Insurance Review 44(1): 54–86.

Hallegatte, S (2012), “Toward a world of larger disasters? Ideas for risk-management policies”, VoxEU.org, 14 April.

Harrison, D M, G T Smersh and A L Schwartz (2001), “Environmental determinants of housing prices: The impact of flood zone status”, Journal of Real Estate Research 21(1–2): 17–38.

Hosono, K, and D Miyakawa (2014), “Natural disasters, firm activity, and damage to banks”, VoxEU.org, August 13.

Kunreuther, H, and M Pauly M (2005), “Insurance decision-making and market behavior”, Foundations and Trends in Microeconomics 1(2): 63–127.

MacDonald, D N, H L White, P M Taube and W L Huth (1990), “Flood hazard pricing and insurance premium differentials: Evidence from the housing market”, Journal of Risk and Insurance 57(4): 654–63.

Maccaferri, S, F Cariboni and F Campolongo (2012), Natural catastrophes: Risk relevance and insurance coverage in the EU, European Commission, Joint Research Center, Scientific Support to Financial Analysis Unit, Institute for the Protection and Security of the Citizen.

Palm, R, and T W Bolsen (2022), “Coastal home buyers are ignoring rising flood risks, Despite clear warnings and rising insurance premiums”, The Conversation, 25 March.

Santato, S (2013), The European Floods Directive and opportunities offered by land use planning, Climate Service Center.

Sigma (2021), Natural catastrophes in 2020, Sigma Report, Swiss Re Institute.

Skantz, T R, and T H Strickland (1987), “House prices and a flood event: An empirical investigation of market efficiency”, Journal of Real Estate Research 2(2): 75–83.

.

![]()