On a Wednesday morning in mid-March, the Rams realized they couldn’t be the same as before.

That day, a group that included general manager Les Snead, head coach Sean McVay, defensive coordinator Raheem Morris and the pro personnel tandem of John McKay and Matt Waugh, clustered together in one of the small offices at the team’s Thousand Oaks, Calif., facilities.

They were just a few weeks removed from winning Super Bowl LVI, and the glow of their 2021 season hadn’t quite left the building. One wall in the team meeting room still featured a glossy, enlarged photo of defensive tackle Aaron Donald’s hit on 49ers quarterback Jimmy Garoppolo that helped seal the NFC Championship Game, pinned up in accordance with a weekly tradition to commemorate the season’s big plays.

The cries of “run it back!” from the men in that office, echoed by dozens of players and coaches during their boozy, confetti-freckled championship parade, were still ringing in their ears that Wednesday when Von Miller told them he wasn’t coming back.

A future Hall of Fame pass rusher whose historic postseason helped the Rams win their first title in Los Angeles, Miller had wanted to test free agency that spring for the first time in his 11-year career. But he told the team shortly after the parade that he’d be back, so long as the Rams got the money right on a previously-discussed contract extension.

Miller’s return would mean keeping the Super Bowl band together, “running it back” with the same group. Executives already knew McVay would be around for the attempt at a repeat despite rumors he was considering stepping away for a massive broadcast deal. They laid out frameworks for extensions for quarterback Matthew Stafford and top receiver Cooper Kupp, as well as a restructure and raise for Donald.

But then, the call came in. The Buffalo Bills, who had come excruciatingly close to playing the Rams in the Super Bowl that season, had offered Miller something L.A. would not. Miller was heading to another contender.

Snead quietly pushed back his chair and left the room. He needed to take a walk.

When he returned, everything would change.

In November 2021, receiver Robert Woods tore his ACL in practice the day after the Rams signed Odell Beckham Jr., a prolific receiver still reeling from his controversial exit from Cleveland. Instead of gradually working Beckham Jr. into the offense, he had to contribute immediately. But the Rams couldn’t simply put him in Woods’ own unique role — running jet sweeps, blocking and executing the catch-and-run shorter passes and midfield crossers off of play-action that were once a signature of the McVay offense.

The Rams weren’t playing that way so much anymore anyway. With Stafford, McVay moved away from play-action and toward more dropback passing concepts, shotgun and empty formations with every eligible pass-catcher aligned along the line of scrimmage pre-snap.

It was a slow, at times frustrating process to overhaul their offense minus Woods amid the unforgiving sprint of a season that started to feel like quicksand. The Rams had started 7-1 but went winless in November. It was only when the coaching staff decided to swap out their traditional run game with a power-run plan, utilizing extra offensive linemen as “tight ends” in jumbo-blocking formations for steady downhill back Sony Michel, that the team began to re-discover its heartbeat.

“Heck, OBJ didn’t even know the playbook,” Snead told The Athletic. “As Big Whit (left tackle Andrew Whitworth) would say, ‘When in doubt, when taking on water, let’s just run at ’em. Let’s play bully ball.’”

The Rams also learned something important about themselves and their agility.

“I remember the energy,” Snead said. “It can be frustrating — you can have this theory, this vision, that no matter the adversity we’re dealt, somehow we’ve got to figure out how to be stronger out of it. But there are times when you’re in the valley, when that (theory) can be a sign on the wall … can you actually pull it off?”

Stability via the run game helped the Rams put together a five-game winning streak in December and January. As they steadied, they regained the ability to test out new possibilities with Beckham in their passing game

“I mean, what Odell did last year was unbelievable,” said Kupp, who went on to win the ultra-rare receiving triple crown in 2021. “I just can’t imagine learning the offense the way he did in the middle of having to play the game. It was an incredible thing. … You get to the place where it’s like, ‘Hey, we need to figure out what that’s gonna look like,’ he provided something that was pretty special.”

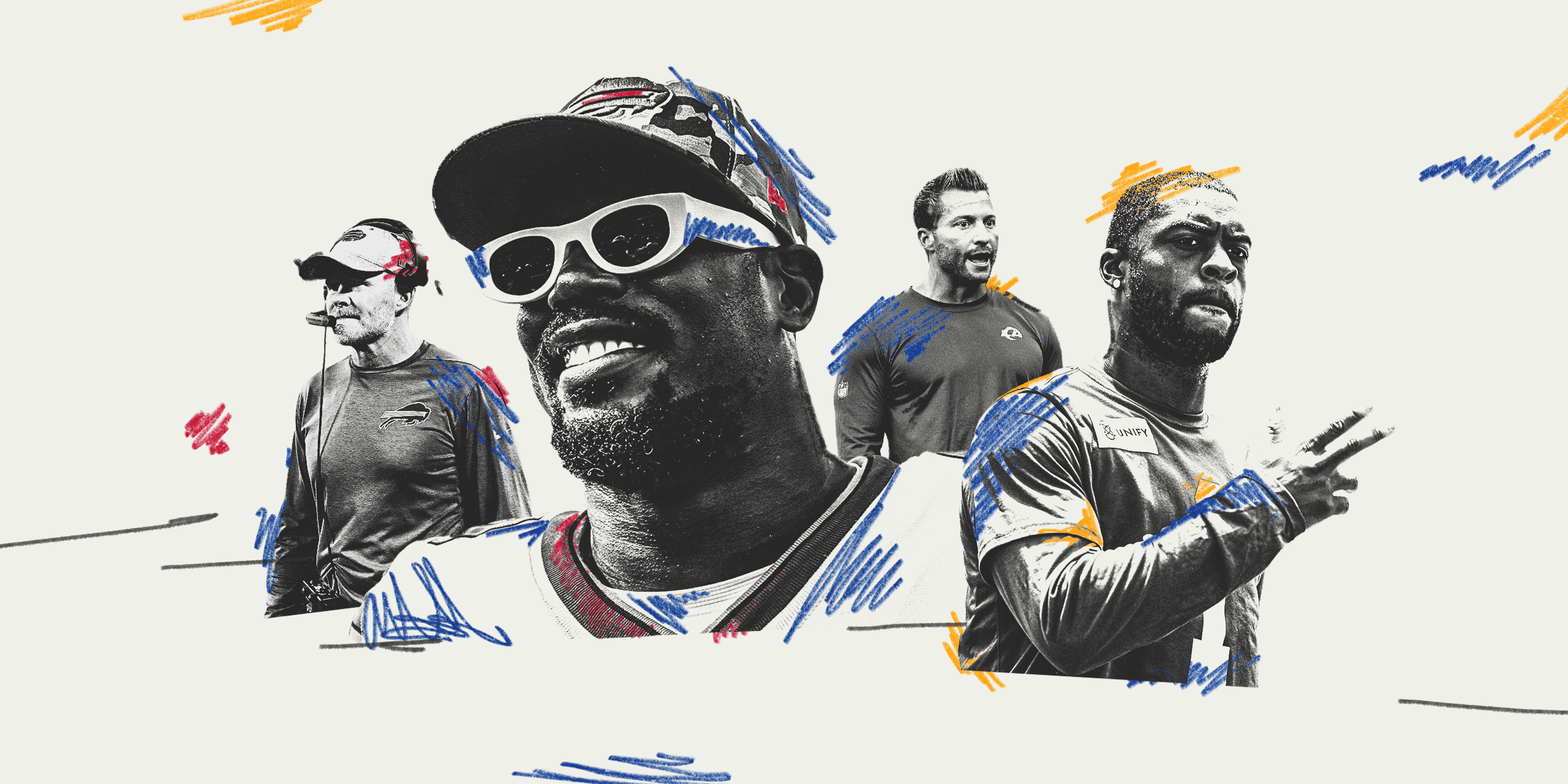

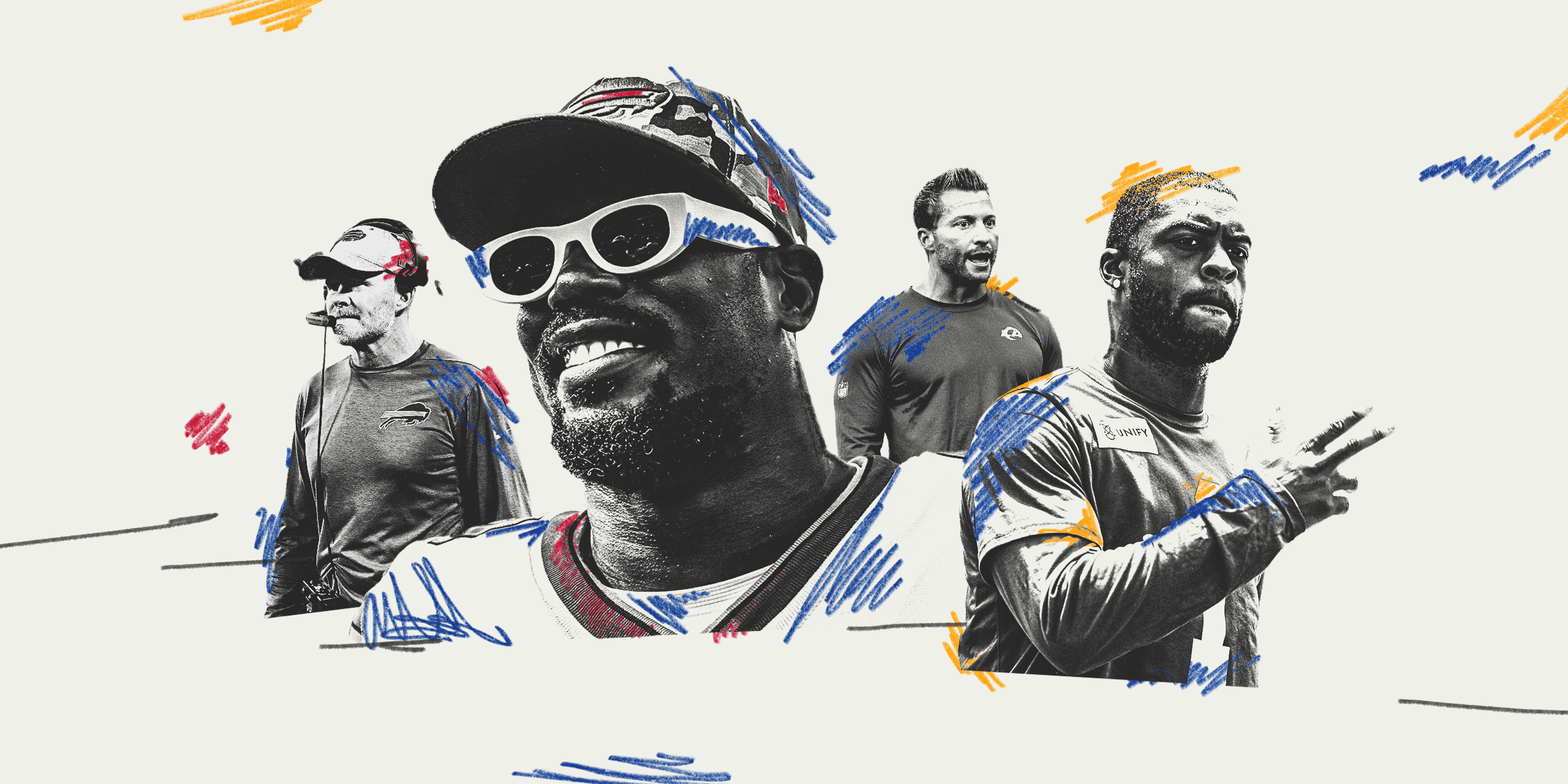

Von Miller’s contributions to the Rams’ Super Bowl run illustrated the Bills’ biggest offseason need. (Joshua Bessex / Getty Images)

The Rams had traded for Miller days before signing Beckham, believing the pass rusher to be the final piece needed for a roster that seemed to have a deep postseason run in its destiny — and elite quarterbacks in its path.

Miller arrived in Los Angeles with a minor ankle injury but got healthy through the Rams’ bleak November. In December and January, he started to come alive as the Rams regained their own footing. He began sitting beside Donald on the team plane after road games and plotting new rush patterns with defensive line coach Eric Henderson.

Meanwhile, the Bills were gathering momentum of their own. They won their last four regular-season games and throttled the rival Patriots in the AFC Wild Card round, scoring a touchdown on each of their first seven drives.

But in the divisional round against the Chiefs, Buffalo found only heartbreak. All too comfortably, Kansas City quarterback Patrick Mahomes led a now-infamous 13-second game-winning drive in overtime as the Bills’ pass-rush failed to rattle him. Their season over, Buffalo GM Brandon Beane and head coach Sean McDermott watched as the Rams’ own pass-rush found a higher gear as they advanced. Miller topped the NFL in pressure rate through the playoffs, recording 12 tackles (six for loss) and four sacks, two of which came in the Super Bowl win.

If the Bills weren’t already painfully aware of their missing piece, Miller and the Rams made it all too clear.

“We obviously know how close we were the last two years. AFC Championship, and then this year 13 seconds away from going back to the AFC Championship,” Beane said this spring. “That’s not our goal. Originally, our goal was to win the division, get to the playoffs and get a chance. We’ve done that. Now we gotta find how we get to that next step. …

“The quarterback is the premium position. We have that. The next thing is to get someone who can get the other quarterback down.”

Multiple league sources believe the Bills were initially targeting veteran pass-rusher Chandler Jones as free agency began in March — not necessarily out of a preference (the Bills had inquired about trading for Miller ahead of the 2021 season), but because everybody, including the Rams, believed Miller was returning to Los Angeles. But as the “legal tampering” period opened and the March 16 official start to free agency loomed, Jones emerged as a match for the Las Vegas Raiders.

The Bills became aware of a key contractual detail missing from the Rams’ still-unsigned offer to Miller: A third year of guaranteed money. The Rams wouldn’t — and couldn’t — do that. They had never offered a third guaranteed year to a player, and they couldn’t set a precedent for Miller instead of homegrown stars Donald and/or Kupp, both of whom had deals looming later that spring.

Miller called McVay and told him he was accepting the Bills’ six-year, $120 million offer with a little over $51 million guaranteed over three years. Some in the room sat for a moment, stunned by Miller’s change of heart. Snead wasn’t the only one who needed to take a walk.

The Rams were forced to pivot, but they weren’t going to target another pass rusher if they couldn’t get one they felt was worth a high-capital investment. A key element of their team-building model is only investing on that level at certain positions — quarterback, pass rusher, cornerback and receiver — and only in players they believe have “elite” traits as quantified by their in-house analysis.

“What we can’t do is mope that we don’t have Von,” said Snead, adding, “We’re not replacing Von.”

The group immediately turned on some film of free-agent cornerbacks but weren’t inspired. Then, McVay flipped through a few texts on his phone. On and off that spring, he, Stafford and Kupp had talked about free-agent receiver Allen Robinson, marveling at what they felt others couldn’t see: that Robinson, for all of his reputation as a high-point, contested catch receiver, was incredibly versatile. That he could separate in between the hashes, not just up in the air. That, along with all of that, Stafford always loved having a big-bodied receiver with a huge catch radius to reel in what McVay admiringly calls, “f— it throws”.

“You can line (Robinson) up anywhere,” said Kupp. “He can do all of the other stuff, just like Odell was doing. Play some stuff underneath, be able to be singled up on the back side and win one-on-ones — I mean, A-Rob is a guy who can do all of it.”

McVay was nervous about his receiving corps. Beckham, playing on a one-year deal, tore his ACL in the Super Bowl en route to what may have been an MVP performance. The Rams wanted (and still want) to bring Beckham back but knew he couldn’t contribute until November or December. No. 3 receiver Van Jefferson had just undergone the first of two knee procedures. Woods was still recovering from his torn ACL and so was considered by staff as an “unknown” for 2022.

The energy in the room started buzzing as the group turned on film cut-ups of Robinson. Still, the Rams were cautious. They knew they couldn’t offer him more than the framework they had set aside for Kupp. They also figured he had a couple of suitors already. Would he consider them?

Late that Wednesday night, the Rams called Robinson. He was deep in talks with the Eagles, two sources told The Athletic, but the Rams asked him to postpone his final decision long enough to get on a video call with McVay and Stafford. The coach and quarterback showed Robinson clips of Beckham that they had hustled to put together for the occasion showing how the passing offense eventually evolved around him and Kupp.

“Didn’t know if he was going to be here or not,” Stafford said. “But tried to put some stuff out there to show a role that could come to fruition.”

A 2014 second-round pick who spent the first eight years of his career split between the Jaguars and Bears — two teams with woefully inadequate quarterback play — Robinson had taken a cautious and researched approach to free agency. Along with his agent, Brandon Parker, he even attended the 2022 scouting combine in late February to talk to interested teams in person.

When the Rams called, Robinson didn’t need to be sold — a Detroit native, he had long admired Stafford from afar. But he let McVay and Stafford say their piece. After watching the clips with them, Robinson decided that throwing himself into something he hadn’t expected gave him a feeling he’d been waiting for, for almost a decade.

“I think for (some) guys, that ‘unknown’ causes sleepless nights,” he said. “At the end of the day, you just believe in yourself, you bet on yourself, you trust in yourself and you believe that what happens next is best. You never know what’s on the other side.”

Only a couple of hours after their initial call, Robinson told the Rams he was in. The sides agreed to a three-year, $46 million deal with $30 million guaranteed mere hours after Miller’s fateful call to McVay. The sudden change in strategy — not from pass rusher to pass rusher, but from elite defensive player to elite offensive player, was striking.

“We love Von, but it didn’t work out,” said McVay. “And so now, you say, ‘How do we pivot in the right direction?’ And it doesn’t exclusively have to be from that position. I think that’s where the flexible approach from our personnel staff, our coaches (is) to say, ‘OK, what does that look like?’”

Shortly after Robinson signed, Woods was traded to Tennessee. The Rams, by then emotionally removed from the idea of “running it back”, leaned further into their new direction. They signed another future Hall of Famer, inside linebacker Bobby Wagner, in late March, rolling some of their savings from not signing Miller into Wagner’s multiyear deal.

“Then, it was like, ‘OK, this is going to be a different team,’” COO Kevin Demoff told The Athletic.

“I think if you’re a realist about repeating, defending, the fact that nobody has done this in 17 years — if there was a way to do it, people would have figured it out,” he added. “So clearly, the way to do it is to not pay attention to repeating, and to pay attention to building the best team that you can.”

McVay says it’s an ethos of agility. Snead likes to call it “being anti-fragile.”

It’s the same phrase Snead repeated back in November, when the Rams almost broke, but instead — behind Beckham and an unexpected pivot in their offense during an adverse time — found something new.

Signing free agent Allen Robinson was consistent with the Rams’ team-building model of investing in stars at premium positions. (Jevone Moore / Getty Images)

The lore inside the Rams locker room is that Robinson and Wagner respectfully declined open invitations to attend the team’s ring ceremony in July.

The two attended every single day of voluntary spring workouts. Wagner sat with different players in stretching lines before the start of practices. Robinson dove into the playbook with restless, obsessive energy. Personnel staff marveled at the intensity with which he studied.

But they told teammates they wanted to build something new together. The past was not theirs to live in.

“People want to come here and win and do something special,” said Snead. “I think that’s a little bit of an unsung ingredient. Now, time will tell, but I do think it’s neat having players like that.”

The Bills know that, too. It’s part of why they went after Miller. In a way, they and the Rams are linked not just by Miller, or by the NFL’s schedule, but also by a similar ethos: They are in Super Bowl contention, and willing to sprint without abandon toward whoever they believe gets them that much closer to eternity.

“As soon as you take that step (in one direction), I think it’s your duty to ask, ‘Is this still the right way to go?’” said Kupp. “You still keep asking yourself that, (even as) you keep going as fast as you can, as hard as you can down that way.”

The cries of “run it back” that reverberated through the hallways and spilled onto the fields in Thousand Oaks are gone, replaced by a new feeling.

It stems from the moves the Rams made to win a championship in 2021, from the attitude by which they built their team, from a mantra Whitworth imparted throughout a bleak November before the Rams went on their run, from an offseason in which nothing stayed the same because it couldn’t, perhaps because it shouldn’t:

“Grow or die.”

(Illustration: John Bradford / The Athletic; Photos: Grant Halverson, Aaron Ontiveroz, Harry How, Scott Tatsch / Getty Images)

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘dataProcessingOptions’, []);

fbq(‘init’, ‘207679059578897’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’); .