Anna Reddy, a retired teacher from Bengaluru, is living free in the autumn of her life. She has downsized and moved into a 320 sq. ft tiny home that has been upcycled from an old shipping container. Having lived through the loneliness of a lockdown and waking up to the need for smart budgeting as a pensioner, she has chosen to be resource-conscious without feeling the pinch. So, she’s leased a patch of land on a friend’s farm far out of the city, parked her pre-fabricated home on an outcrop overlooking a lake, plushed up the interiors and wrapped herself with a huge sun deck. Apart from sleeping, cooking and chores, she spends sunrise to sundown outdoors, tending to her organic garden, attempting some landscaping with rocks and foliage, writing a blog on the patio, lounging with her dog, dining with friends under the stars and watching the season change colour. “Can we make room for something more meaningful in our lives than clutter it with things that one has no use for and spaces that are unmanageable?” asks the 58-year-old.

Not far down the road are Rohit and Maya Chinnaswamy, both software professionals in their late 20s, who have a tiny home of their own in a land bought years ago by their parents. Just married, and with COVID-19 giving legitimacy to a work-from-home culture, they have created their oasis without the burden of EMIs, living rich rather than squeezing themselves into a city apartment. “Minimalism is not about giving up, it is about choosing what you need. We don’t have the big TV wall but we have a bigger drop-down projector screen,” says Rohit.

The interiors of Habitainer’s Jade Garden, Bengaluru (Credit: Habitainer)

The interiors of Habitainer’s Jade Garden, Bengaluru (Credit: Habitainer)

The tiny-house movement, which advocates a “living with less philosophy”, is no longer an alternative way of living. As cities bulge out of the seams and shrink the greens, tiny houses are being seen as a sustainable, energy-saving and low-carbon footprint reality than an option. In India, where homes are repositories of memories, collectibles and heirlooms and the acquisitive measure of success, we seem to be right-sizing our mindset where bigger does not mean better and less is more.

Buy Now | Our best subscription plan now has a special price

Reddy says she had to cut her belongings by one-third. That wasn’t difficult. “I hadn’t used them in years. But I kept my books. My ‘smart’ kitchen is bigger and more functional. Maintenance fees and bills are now less than half, I am debt-free and can spiff up my home in 15 minutes. My house is small, but I am living big,” says Reddy, who’s working on a wildflower project with the locals. And should she choose to move elsewhere, to the hills or coast, she can dismantle and reassemble her modular home.

So what is a tiny house? According to the 2018 definition by the International Code Council in the US, it is a dwelling unit with a maximum of 37 sq. m (400 sq. ft) of floor area, excluding bedroom lofts and mezzanine fitouts. But they stretch outdoors with extended porches, leading the inside to the outside. It is debt-free living (the price range varies from Rs 6 lakh to Rs 25 lakh depending on embellishments) and low-maintenance. Some day, it will run off-grid, with solar energy and harvested rainwater.

Okno Modhomes Swiss chalet-style wooden villas at Gandipet near Hyderabad (Credit: Okno Modhomes)

Okno Modhomes Swiss chalet-style wooden villas at Gandipet near Hyderabad (Credit: Okno Modhomes)

With space optimisation a challenge for city planners, tiny homes are seen as a way of future-proofing our existence on this planet. And now that industrialists like Anand Mahindra are backing Chennai-based Arun Prabhu NG, who built a portable house on an autorickshaw, and furniture major IKEA is running a pan-India “Tiny House Project” since 2019, the trend has caught on. The endorsement by Tesla chief Elon Musk, who described his rented one-room pad at Boca Chica, Texas, “more homey”, and with Netflix and YouTube propagating the movement, conspicuous consumerism is no longer aspirational but a societal vice. In resource-starved times, bigness is about letting go and making healthy space for the next generation. Alternative living is an experiment but considering that between 2014 and 2018, the average apartment size in seven major Indian cities shrunk by 17 per cent, according to a study done by ANAROCK Property Consultants, the tiny-home movement is carving out its niche in our realty market. The US-based Jay Shafer, who started his company, Tumbleweed Tiny House, in 1999, is today feted as an icon by millennial tiny-home builders in India.

“Owning a big house is a socio-cultural statement and a small house has so far been seen as a second home. Most of our pre-fabricated homes were being used in resorts and country estates with owners renting them out for Airbnb guests. Post-pandemic, more people want to live in them permanently. With tech-enabled features and plush comforts, we have built more than 200 houses in two years. We’ve even located one in Hyderabad’s posh Banjara Hills. And while south India had woken up to the concept for some time, we are now getting orders from the north as well,” says Payal Jindal, co-director of Loomcrafts, which builds steel module homes with patented technology and stylised interiors.

After the customer chooses the layout and design, a unit is completed, from chassis to electric wiring and interior fitments, at the factory within 90 days. “Steel limits the use of other materials, is structurally strong and requires low-cost insulation in the form of fiberglass blankets, which are fire- and sound-resistant. And while we make trailer houses for international customers, here we place them on a cemented plinth. We then plug in the water and electricity lines that are available in farmlands or leased community land,” Jindal adds. Loomcrafts offers an all-weather guarantee for 50 years.

The interiors of Habitainer’s Jade Garden, Bengaluru (Credit: Habitainer)

The interiors of Habitainer’s Jade Garden, Bengaluru (Credit: Habitainer)

Bengaluru-based The Habitainer makes luxury container homes with flippable sofa-beds, bar-cum-tables, extendable kitchen counters, and customised refrigerators. Inspired by the high demand, its director Gaurav Chouraria is now exploring possibilities of setting up India’s first tiny-home community where investors can lease their own little green patch and set up their homes. “We have done 70 projects in 62 locations across the country in the pandemic years. Of these, only two are offices, the rest are homes. Many have taken to the idea of living permanently in container homes after their staycations at Air bnbs during the pandemic,” he says. The company buys containers at port auctions, using 20 ft x 8 ft for regular homes and 40 ft x 8 ft for premium ones. “There’s a 27-point checklist. For example, we won’t use containers that have carried radioactive material or chemicals. We then strip it down and insulate it with aircraft grade rockwool. High ceilings control ambient temperature and doors, skylights and windows ensure cross ventilation. People mistake tiny living as a cramped-up compromise or forced minimalism. But the basic idea is to stay indoors as little as possible and pursue activities outdoors,” he says.

While this may seem more apt for single people, empty nesters and young people, Chouraria dispels such misconceptions. “The fluidity of adding or joining more containers on your land means that families can actually stay close to each other while maintaining privacy. And since these houses are portable, you can take them as you move or sell them online should your priorities change. You can reuse, recycle and renew,” he says.

Interiors of Caesar Fernandes’ Goa home (Credit: Caesar Fernandes)

Interiors of Caesar Fernandes’ Goa home (Credit: Caesar Fernandes)

Chouraria is now tying up with camping operators to strengthen his revenue stream in the travel industry. Like Tejaswi Rajanah, who owns a five-acre guava plantation, an hour-and-half drive away from Bengaluru. He’s parked a 160 sq. ft single container with a 200 sq. ft of porch called The Little Ranch. “I rented it out during the pandemic at Rs 1,000 a day with discounted deals for staycations. Overlooking a valley, it has good mobile network connectivity where you can comfortably ‘work from nature’,” he says. The Little Ranch was built using a used shipping container, which usually goes into scrap.

Two 23-year-olds from Hyderabad, Harshit Puram and Parikshit Linga, are working with wood while building vacation homes in Gandipet on the outskirts of Hyderabad. Launched in April this year, Okno Modhomes builds Swiss chalet-style homes with atrium-high ceilings in 90 days. They import guilt-free wood, from New Zealand, Finland and Norway, which means that for every tree cut, four more have already been planted. “Besides the cellulose and water are extracted in such a way that no termite and moisture can get into them. Cement attracts and radiates heat, wood does the reverse,” says Puram. Leak proof, synchronised with cloud-based voice service Alexa and fitted out with IKEA, these span between 300 and 500 sq. ft. It is the only project to be recognised by the Indian Green Building Council.

The Little Ranch by Tejaswi Rajanah, on the outskirts of Bengaluru (Credit: Tejaswi Rajanah)

The Little Ranch by Tejaswi Rajanah, on the outskirts of Bengaluru (Credit: Tejaswi Rajanah)

Caesar Fernandes, CEO, Wooden Homes India, himself lives in a pre-fabricated 800 sq. ft home. He, too, imports certified red pine and spruce planks, arguing that the Scandinavian cutting technique reduces wastage. “Our wood panels are interlocking. And apart from treating the wood every two years, there’s no maintenance really,” he says.

As tiny homes dot the margins of our big cities, and in the absence of Western-style building codes, what are the legalities involved in building one? Fernandes says, “Given their portability, tiny homes are considered temporary structures and do not come under civil construction laws. Usually, people rent farmlands or take advantage of farmhouses owned by friends and relatives but leasing land, particularly in tier II and III cities, where there are controlled green zones (non-residential zone) with 10 per cent allowed for housing, is a possibility. But we need revision of building byelaws to dedicate new zones for 160-300 sq. ft living.” Nevertheless, a beginning has been made. Simplicity, according to Renaissance Man Leonardo Da Vinci, “is the ultimate sophistication.”

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

.

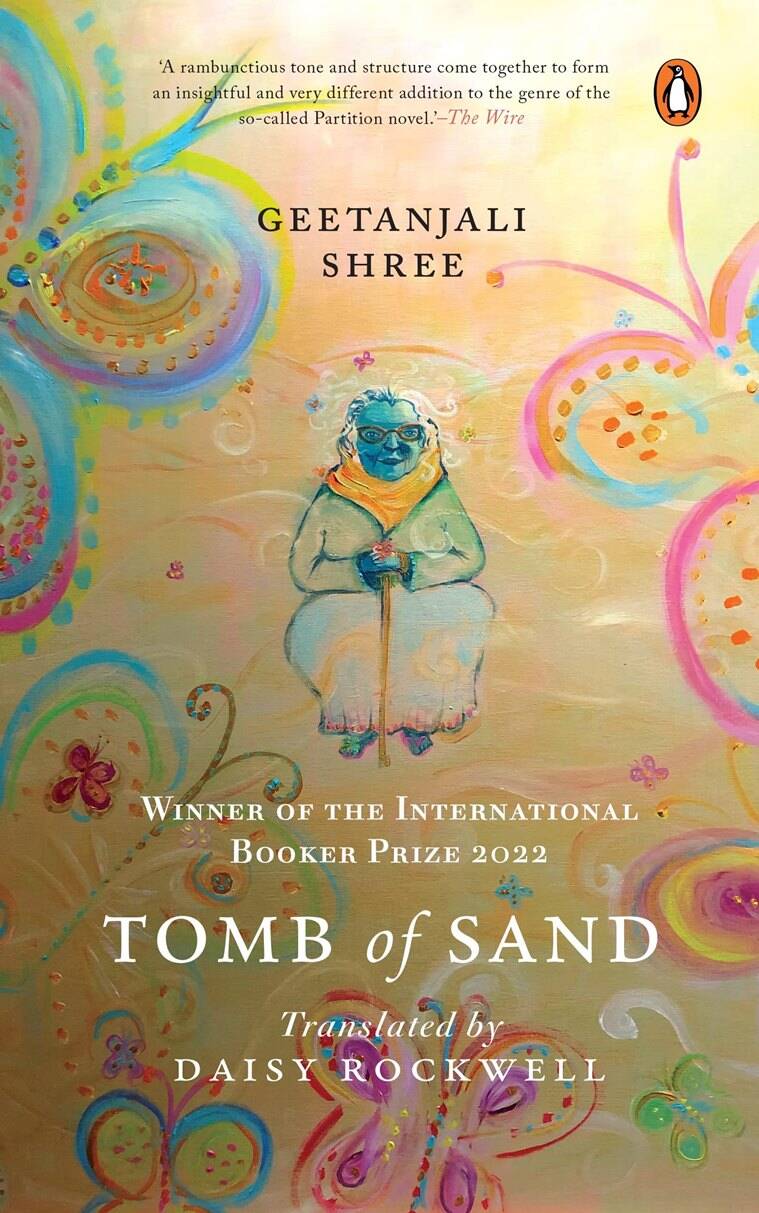

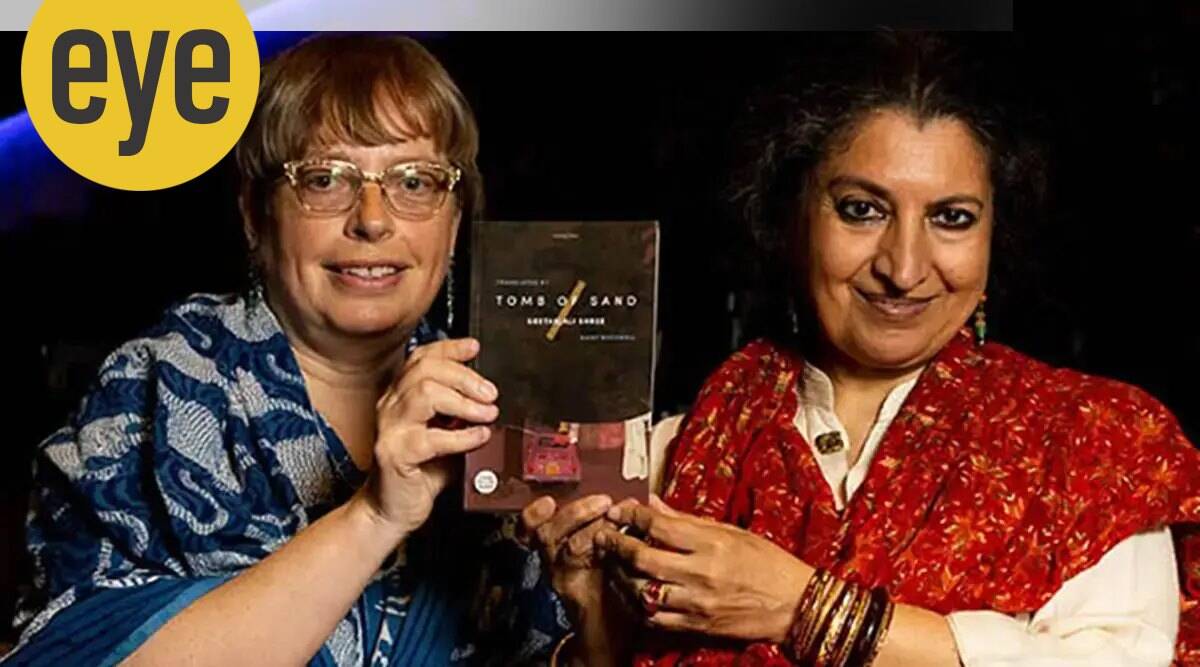

Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree; Translated into English by Daisy Rockwell; Penguin Random House; 696 pages; Rs 699 (Source: amazon.in)

Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree; Translated into English by Daisy Rockwell; Penguin Random House; 696 pages; Rs 699 (Source: amazon.in)

A clip from Usha Jey’s hybrid Bharatanatyam viral video. (Photo credit: @signature.ch)

A clip from Usha Jey’s hybrid Bharatanatyam viral video. (Photo credit: @signature.ch)