IT is early days, this is a state known for too many false starts and yet the buzz this time is unmistakable.

A little over 1.6 km from Zero Mile in Begusarai, there’s the hum of new life as workers load cases of soft drinks, packaged water and fruit juice on trucks lining a 53-acre sprawl. About 200 km to the east, a former brick-kiln owner is juggling “at least 200 calls every day”, from farmers, traders, suppliers and job-seekers ready to sign up for the new ethanol plant he is promoting in Purnia.

“This is just the beginning,” says Bihar’s Industry Minister Syed Shahnawaz Hussain.

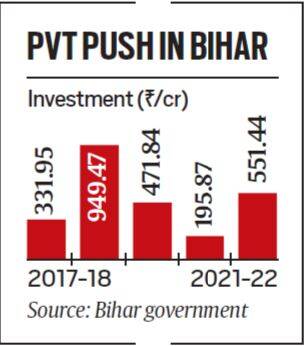

Over 15 days in April, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar inaugurated two showpiece private ventures — a Rs 500-crore Pepsico bottling plant, one of the biggest of its kind in India, and a Rs 105-crore ethanol plant. This marks the first time under Nitish’s government that big-ticket projects have taken off in Bihar, a key milestone given that he has remained at the helm for nearly 17 years now.Best of Express Premium Premium

Premium Premium

Premium Premium

Premium Premium

Premium

“We have relaxed norms with a single-window system for promoting such industries. In the next two years, we expect dozens of such industrial units to come up,” says Hussain.

Today, both the plants have hit the ground running — the Pepsi plant being a case in point.

It was on April 15 that the Chief Minister inaugurated the four-line plant, the first of its kind in Bihar, which can produce 36,000 bottles and about 1.25 lakh cases in a day. “We had some apprehensions about law and order, given Begusarai’s background, but we are very happy to start our biggest plant between Kolkata and Jamshedpur,” says Manoj Dwivedi who heads the plant owned by Pepsico franchisee Varun Beverages Ltd (VBL).

“The Industry Minister helped us speed up the process and we got the 55-acre plot for just Rs 26 crore on a 99-year lease. We have a four-line plant producing bottled water, carbonated soft drinks (CSD) in PET (plastic) bottles, packaged juices and bottled soft drinks,” he says.

🚨 Limited Time Offer | Express Premium with ad-lite for just Rs 2/ day 👉🏽 Click here to subscribe 🚨

The speed that Dwivedi refers to is what marks out the state’s renewed industrial push — in this case, just 10 months. After land possession was cleared on June 25, 2021, construction started on June 28, 2021, the lease deed was executed on March 6, 2022, and the plant started operations on April 15, 2022.

Bihar had earlier just a single-line Coca Cola bottling plant near Patna and a single-line Pepsico plant run by another franchisee in Hajipur. “After the franchise in Hajipur refused to give its one-line plant to us, we decided to build a much bigger plant independently… and settled on Barauni in Begusarai. We have good access to roads and the electricity supply is very good. We are currently producing 60,000-70,000 cases of CSDs, packaged water and juice per day and cater to Bihar and a good part of Jharkhand,” says Dwivedi.

Outside the USA, VBL is one of the largest franchisees of PepsiCo. And overall, the Barauni plant has an annual capacity of 16.22 million cases of CSD, 8.34 millions cases of packaged drinking water and 7.02 million cases of juices beverages. The company is now planning to start work on phase two — another four-line plant. At the Barauni plant’s inauguration, Nitish Kumar had requested VBL founder Ravi Kant Jaipuria to explore the possibility of making mango, litchi and banana juice.

The obvious benefit of the plant is employment for local youth. “We need ITI and B.Tech (mechanical, electrical, and electronics and communications) graduates. An ITI degree holder can get Rs 10,000 to Rs 25,000 per month and a B.Tech Rs 25,000 to Rs 70,000. But as the plant uses the latest robotics technology, with automation and AI, there is not much scope for direct employment. We have about 65 direct employees and about 700 indirectly involved,” says Dwivedi.

One of the job aspirants here is Shyam Kumar, a B.Tech degree holder, from Beguserai. “Now that we have a big industry in our backyard, youths like me have opportunities at home. We hope the plant expands fast and employs more people,” says Kumar.

Inside the plant, VBL officer Gaurav Mishra maps the seven-step process of making soft drinks — from the tube that is blown up into a bottle, to the giant conveyor belts, and the trolley lifting up the five-level stack of final stock.

It’s a fully automated process with quality engineers keeping an eye on every step. “There are instances when the entire production is stopped if the syrup and liquid is not prepared as per specification,” says Mishra.

In Purnia, key word is ethanol

Automation is the operative word in Purnia, too, where the first grain-based greenfield ethanol plant has come up. “The place where we have set up the plant, on 15 acres, used to be a brick kiln. Today, farmers and traders in maize and broken-rice and also poultry and fish feed, byproducts of a grain-based plant, have started flocking to us,” says Vishesh Kumar Verma, one of the promoters of Eastern India Biofuels Pvt Ltd (EIBPL), adding that the plant needs 170 tonnes of maize/ broken rice daily.

Inaugurated by the Chief Minister on April 30, the plant’s location is tied to the fact that Purnia and neighbouring Katihar, Khagaria and Saharsa, are at the heart of the state’s maize hub. With the Centre’s push for alternate fuel, and its green signal for mixing upto 20 per cent of ethanol in petrol and diesel, Verma is upbeat.

EIBPL plans to buy 130 tonnes of rice husk and 145-150 tonnes of maize or rice from local farmers and traders every day. It will also produce 27 tonnes of DDGS (distiller’s dried grains with solubles) — a by-product of bioethanol fermentation, which will be sold as poultry feed.

“The ethanol will be sold to oil marketing companies namely Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum in Bihar and neighbouring West Bengal and Jharkhand, for which a 10-year term purchase agreement has been signed (with the OMCs),” says Verma.

Then, of course, there are the phone calls to tackle. “At times, it is very frustrating but then I think about how setting up ethanol plants can change the lives of people. Even if one plant is able to take five-10 per cent of maize produced in Purnia, it will bring change. The plant directly employs about 55 people, and provides indirect employment to about 1,000 people,” he says.

According to A P Singh, a principal consultant with Global Canesugar Services which set up the plant and looks after its operations, one quintal of rice produces about 450 litres of ethanol while an equal amount of maize generates about 400 litres.

Leading the team here is B B Pathak, who is the plant in-charge — overseeing the process from the pile of grain sacks at the entry point to the lower tanks where initial sifting is done and the mammoth flash tank where distillation starts after 70 hours of fermentation. The final product is stored in three main tanks, from where it is moved to three smaller tanks for sale.

Workers at the ethanol plant in Purnia. (Express photo by Santosh Singh)

Workers at the ethanol plant in Purnia. (Express photo by Santosh Singh)

“The entire process is automated. We use our own power plant in place of government supply to ensure hassle-free production,” says Pathak, adding that the production technology ensures “zero liquid discharge”.

Says Manish Kumar Choudhary, CEO of Aranyak Agri Producers Company, who visited the plant last week: “We have a huge chain of farmers from whom we can procure grains. We provide linkages and look forward to working with the Purnia plant.” Says Kuldeep Jain, a trader from Siliguri: “I want to purchase DDGS from this plant and supply poultry and fish feed to Andhra Pradesh.”

ExplainedLong waitSince 2006, the Bihar government under Nitish Kumar received over 1,000 investment proposals but barely 30-40 key projects have been fully realised — most units are for food processing and utensils. The reason: Question marks over law and order, and infrastructure such as roads and power.

Local maize farmers are also excited. “Though we can sell maize in Gilab Bagh in Purnia, which is a big grain market, this plant can buy our sub-standard grain as well,” says Shanker Singh, from Kritya Nand Nagar in Purnia.

“Our main focus is to open as many ethanol plants as possible,” says Industry Minister Hussain. “We have 16 plants lined up and many more proposals are at different stages of clearance. Ethanol plants can write Bihar industry’s turnaround story.”

According to officials, investment proposals worth Rs 30,382 crore were received for setting up 151 units under Bihar’s ethanol production promotion policy. But due to less quota, only 17 units are being established in the first phase.

Bihar’s current annual ethanol supply quota to OMCs is 36 crore litres, says Hussain. “But as per the availability of raw materials and water, Bihar’s ethanol production capacity is 172 crore litres per annum, considering the proposals for investment and other favourable conditions. If Bihar gets the quota according to capacity, not only will the state emerge as the largest ethanol hub of the country, it will also play a very important role in the development of the country’s economy.”

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

.