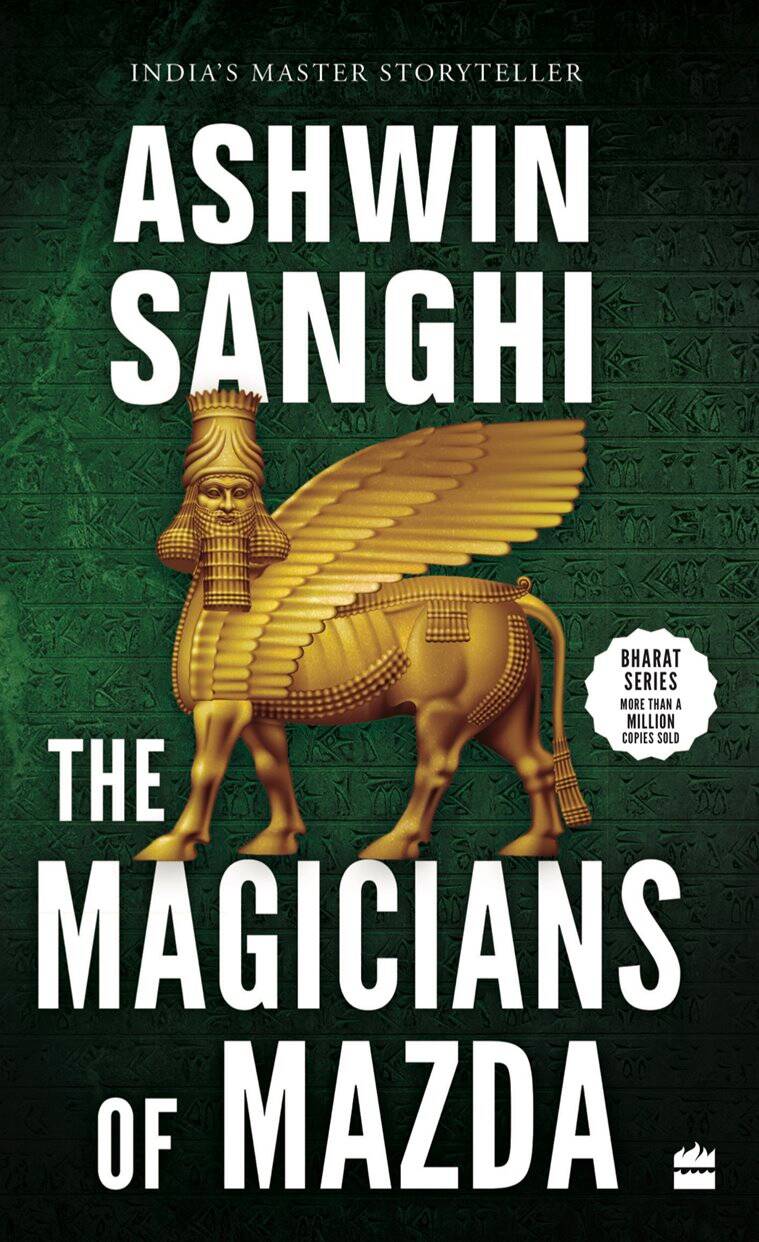

It was a dinner with Dan Brown, a flight with actor Boman Irani, and a barred entry into Mumbai’s Tower of Silence that gestated world-famous thriller novelist Ashwin Sanghi’s latest The Magicians of Mazda (HarperCollins, Rs 450). A globetrotting story of Zoroastrianism, it is centered on an idealistic scientist who invents a panacea for all diseases. Mazda, the seventh novel in the series, follows the nefarious forces — a greedy pharmaceutical, the Iranian government and the Taliban — out to steal the formula from him, exposing unknown secrets of the community’s past.

🚨 Limited Time Offer | Express Premium with ad-lite for just Rs 2/ day 👉🏽 Click here to subscribe 🚨

In 2014, Brown and Sanghi toured Mumbai after a talk at the National Centre for Performing Arts. One of their destinations was Malabar Hill’s Tower of Silence, the Zoroastrian structure for excarnation. “I found it absolutely fascinating that nobody has written fiction on this ancient faith that is a precursor to most Abrahamic religions,” says Sanghi, adding that he sneaked in a small action sequence in the location into his collaboration with James Patterson, Private India, the same year. After finding Irani next to him on a flight, Sanghi told him that he was interested in Parsi history. Irani directed him to the Qissa-i Sanjan, an account of the Zoroastrians who fled Islamic persecution in Iran in the eighth century. Soon enough, Sanghi knew that a novel was brewing.

The research for Mazda, like all of Sanghi’s books, took six to nine months. “There were multiple works I needed to reference because I’m an outsider to the Parsi religion,” he says, rattling off a list including historian Alan Williams, runologist Stephen Flowers and linguist Mary Boyce. As Jim, Mazda’s scientist protagonist, is abducted and carted across treacherous terrains around the globe in a blindfolded haze of planes, trucks and prisons, he reminisces about his family’s history — one that is bound inextricably with his religion’s history itself. “I wanted to structure the story like the peeling of an onion,” says Sanghi, adding, “As the present-day narrative hurtles forward, we retreat chronologically backwards in Jim’s mind as he recalls the tale of Parsis arriving in India, being persecuted in Iran, and the founding of their faith.”

The research for Mazda, like all of Sanghi’s books, took six to nine months. (Photo: Harpercollins)

The research for Mazda, like all of Sanghi’s books, took six to nine months. (Photo: Harpercollins)

Delivering this history without weighing down the narrative is crucial to the momentum that Sanghi builds, a trait that contemporary teaching of history would do well to incorporate, he says. “We are living in a world of so much technology and content, yet we persist with boring text books. You now have so many movies, web series, illustrated comics and novellas on various subjects. History should be made three dimensional,” he says.

But it’s not just history that is remixed in Sanghi’s books — contemporary reality is always around the page’s corner. The COVID vaccine crisis in India, where doses were split between the government and private hospitals, along with patenting conflicts between various countries, inspired Sanghi to create a scientist who could place social good above private good. “We were seeing certain companies put crazy conditions on governments in order to supply vaccines. So I thought, what if Jim is one such weirdo who wanted to make his cure free to all?”

But, of course, scientific quandaries are not the only ones a writer of mythology and history has to deal with. Even though he frequently delves into cherished stories and iconography and laces its gaps with fiction in his work, Sanghi says that if you approach the matter with sensitivity and enough research, there is little reason for anyone to get offended. “I also provide a bibliography in all my books because mythology, history or theology often has a single version and my references will contain material that goes contrary to what I’m talking about in the book. If you are digging deep enough, you will probably find a contrarian version,” he says.

Sanghi reads history as a cluster of multiple narratives. He says that people demanding mosques to be surveyed while scholars contest the same claims of demolished temples is a backlash to “only one historical narrative dominating the public” since 1947. “We never had something like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that South Africa set up after the Apartheid. The idea that history can be completely unbiased is nonsense. The only way we can remove bias is by having all narratives flourishing,” he says.

Elaborating on the role fiction plays in studying the past, he says, “With my books, I take obscure bits of history, religion or theology that have been ignored and try to bring them into the mainstream. This is to tell scholars that look, I am no scholar, I am no historian. But you guys are. So why haven’t you looked at this?”

📣 For more lifestyle news, follow us on Instagram | Twitter | Facebook and don’t miss out on the latest updates!

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

.