THREE MONTHS back, Kimcham Taiju says, she made the “bravest decision” of her life: she signed up her husband for a drug de-addiction programme.

For 25 long years, Taiju’s husband, like many in his village, was addicted to ‘kaani’ — as opium is colloquially referred to in Arunachal Pradesh’s Changlang district. But one Sunday evening in March, Taiju and the other women of the village gathered at the local community hall, and decided that “enough was enough”. A list of 50 names was drawn up, and submitted for the district administration’s month-long drug de-addiction programme.

That night, Taiju broke the news to her husband. As did Damlop Jongsam, Asem Taijong and scores of women in the village of Old Changlang, whose spouses were addicts. “Jaabi ne? (Will you go),” Taiju recalls asking him. “Jaam de (I will),” was his answer.

Recovering addicts playing volleyball at de-addiction camp at Bordumsa. (Express Photo)

Recovering addicts playing volleyball at de-addiction camp at Bordumsa. (Express Photo)

The men were sent 100 km away, to a de-addiction facility in Bordumsa town. The women say the plan worked because “no one was singled out”. “They knew they were going together,” says Taijong, in her 40s. “Now, there is hope that Changlang will become drug-free one day.”Best of Express Premium Premium

Premium Premium

Premium Premium

Premium Premium

Premium

Located in India’s easternmost periphery, Changlang has long contended with an addiction problem. Since March last year, the district administration has been trying to find a solution through a model drug de-addiction programme, one village at a time.

🚨 Limited Time Offer | Express Premium with ad-lite for just Rs 2/ day 👉🏽 Click here to subscribe 🚨

It all started in Kengkhu, a village 13 km from Changlang town, when a group of women approached the district’s then Deputy Commissioner, Devansh Yadav, in February 2021, seeking a solution. Just months before, a survey on substance abuse conducted by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment had identified the district as among the 272 most vulnerable in the country, and thus, a focus area of the Centre’s “Nasha Mukt Bharat” campaign.

Recovering addicts doing woodwork at de-addiction camp at Bordumsa. (Express Photo)

Recovering addicts doing woodwork at de-addiction camp at Bordumsa. (Express Photo)

Having held several government-sponsored de-addiction camps without much success in the past, Yadav — who was transferred to Jammu last month after a four-year tenure in Arunachal — knew that the approach had to be different, and formulated a de-addiction programme which would be “bottom up, and in collaboration with the village.”

To that end, Yadav directed the women to activate their Self Help Group (SHG) network, and hold a gram sabha meeting, presided by village elders, where the issue was discussed, a list of addicts drawn up, and the idea of de-addiction suggested. At the end of the meeting, a unanimous resolution was passed: an undertaking by the village to be “drug-free”.

The initiative, titled “Nasha Mukt Changlang”, targeted entire villages, instead of single individuals: the addicts would be sent for a month-long de-addiction programme, either at a pre-existing NGO-run health facility or a temporary one at the village, followed by post-treatment rehabilitation including government-sponsored livelihood opportunities as well as counseling sessions and Narcotics Anonymous meetings. “Since Kengkhu, 17 other villages have adopted the model…and three-four are in the pipeline,” says Yadav.

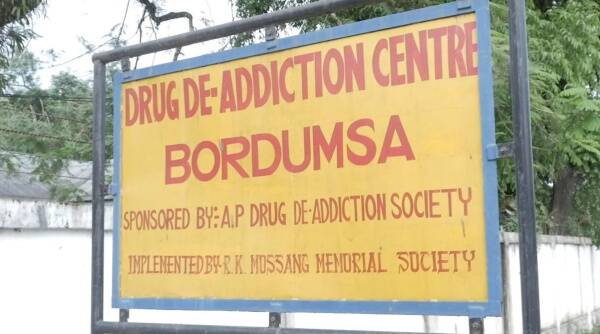

De-addiction centre at Bordumsa. (Express Photo)

De-addiction centre at Bordumsa. (Express Photo)

In April, 50 youths from Bubang village in Khimyong circle finished 25 days at a de-addiction camp. Back in the village, they are now slowly trying to rebuild their lives. As alternative livelihood options for those who have returned from the camps, the administration has provided recovering villages with poultry, piggery and mushroom units to keep them busy.

L Lang (name changed to protect privacy), a 36-year-old former teacher, says the initial days of de-addiction were tough, but he was now feeling better. “Success depends on will. I tried it (opium) once for fun with my friends, and before I realised it, it became a part of my life,” he says.

The addiction is a problem that has its roots in colonial times. “The British encouraged the Singphos (in the northern region of the district) to consume opium to subjugate them. In Tangsa (tribe) areas, near Myanmar, black salt was traded for opium. This led to addiction of the local population. Soon, other synthetic drugs made inroads,” says Yadav.

Changlang and the two neighbouring districts of Tirap and Longding (colloquially referred to as part of the TLC belt) have long been caught in a cycle of drugs and insurgencies: militant groups trade opium for arms.

Despite multiple crackdowns by government agencies over the years, opium continues to thrive, with plantations across these areas. For its part, the government has opened rehabilitation centres, and local police, district administration and women’s groups have organised various awareness campaigns.

De-addiction centre at Bordumsa.(Express Photo)

De-addiction centre at Bordumsa.(Express Photo)

What is different about the new programme in Changlang, as Dihom Kitnya, a 34-year-old social worker from Hatongchu village, points out, is the close synergy of the local community and the authorities. Now that the administration is involved, Kitnya says, things are more “systematic”.

Kitnya’s village signed up for the programme last June. “We heard that the district administration was doing something new, so we got enthusiastic,” he says. Today, Kitnya is the administration’s point of contact on the ground for villages under two circles, Yatdam and Namtok. From persuading people to join the camps, to coordinating with local SHGs, to supervising day-to-day running of the centres, Kitnya spends hours in voluntary service. “Every youth who destroys his life is a loss for our society,” he says.

Posters at De-addiction centre in Bordumsa. (Express Photo)

Posters at De-addiction centre in Bordumsa. (Express Photo)

According to Yadav, the crux of the project lay in understanding that the problem was social, not criminal. “We did not treat the issue as a law and order problem. With addicts, treat them like patients and not as criminals because addiction is a medical problem. They need patience and care,” he says, adding that there were reports of some who relapsed, post-treatment. “Since everyone in the village is involved, it is easy to identify them and work with them again,” he says.

In Old Changlang village, the women say they know it will take a while to become fully drug-free, but the effort is worth it. As Merina Kenga, a social activist and SHG president of the village, put it: “Every other home in our village has an addict. So even if you save one family, it is a feat.”

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

.