BRASILIA, July 22 (Reuters) – Brazilian fixed-income markets are pricing in the highest risk levels in years, raising red flags among investors and government officials who see little relief in sight.While global interest rate hikes and recession risks have put all emerging markets under pressure, Brazil faces special scrutiny after Congress cracked open a constitutional spending cap to allow a burst of election-year expenditures. read more “The problem is the change in the spending cap,” said an Economy Ministry official, who requested anonymity to discuss the situation openly. “It weakens the reading that the fiscal situation will be under control in the coming years.”Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comEven with positive surprises such as strong June tax revenue data on Thursday, the official said Brazil’s yield curve remains under pressure as investors brace for the worst. read more Both major presidential candidates on the ballot in October – leftist former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and right-wing incumbent Jair Bolsonaro – have signaled they plan to extend this year’s boost in social spending into next year.”It’s a fiscal bomb,” said Sergio Goldenstein, chief strategist at Renascença DTVM. “Risk premiums look high, but there is little room for a relevant drop.”The real rate for inflation-linked government bonds has been running at the highest level since late 2016, while Brazil’s five-year credit default swaps are at highs last seen at the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020.Concerns about Brazil’s credit profile come as commodity shocks from the war in Ukraine rattle the global economy and contribute to inflation, prompting rich nations to start raising interest rates.”All the credit spreads in the world are opening, our bonds are not immune to that,” said Ronaldo Patah, chief strategist at UBS Consenso.In fact, Brazil’s strong exports of grains, oil and iron ore give it some advantages compared to other emerging markets riding out the current surge in commodity prices, independent of the political risks in Brasilia now rattling investors.Brazil’s central bank also got an early start hiking rates compared to most peers, raising its benchmark interest rate from a record low 2% in March 2021 to 13.25% currently, with another hike penciled in for August to curb double-digit inflation.Most of the market has therefore been betting on rate cuts supporting growth from the middle of next year. However, risk premiums now point to rates above 13% in the yield curve for maturities ranging from 2024 to 2033, while mid-2023 vertices indicate an accumulated rate above 14%.”I am struck by this process of (yield curve) flattening that we are seeing at a very high level”, said the chief economist at Ativa Investimentos Etore Sanchez.Roberto Dumas, chief strategist at Banco Voiter, said Brazil is caught between a central bank tightening rates while the government is finding new ways to boost spending.”The more one accelerates, the more the other needs to step on the brakes. Everyone is projecting more and more that the Selic will rise more than expected”, said Dumas, who foresees the benchmark rate at 14.25% at the end of this year.Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comReporting by Marcela Ayres and Jose de Castro

Editing by Brad HaynesOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. .

Analysis: Private equity’s swoop on listed European firms runs into rising execution risks

- Boards, shareholders start to rail against lowball bids

- Push for higher premiums compound debt funding dilemma

- Buyer vs seller valuation gaps may take a year to close

LONDON, June 28 (Reuters) – European listed companies have not been this cheap for more than a decade, yet for private equity firms looking to put their cash piles to work, costlier financing and stronger resistance from businesses are complicating dealmaking.Sharp falls in the value of the euro and sterling coupled with the deepest trading discounts of European stocks versus global peers seen since March 2009, have fuelled a surge in take-private interest from cash-rich buyout firms.Private equity-led bids for listed companies in Europe hit a record $73 billion in the first six months of this year to date, more than double volumes of $35 billion in the same period last year and representing 37% of overall private equity buyouts in the region, according to Dealogic data.Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comThat contrasts with a sharp slowdown in overall M&A activity around the world. But as take-private target companies and their shareholders are increasingly bristling against cheap punts which they say fail to reflect fair value of their underlying businesses in 2022, prospects for deals in the second half of the year look less promising.Leading the first half bonanza was a 58 billion euro ($61.38 billion) take-private bid by the Benetton family and U.S. buyout fund Blackstone (BX.N) for Italian infrastructure group Atlantia (ATL.MI).Dealmakers, however, say the vast majority of take-private initiatives are not reflected in official data as many private equity attempts to buy listed companies have gone undetected with boardrooms shooting down takeover approaches before any firm bid has even been launched.”In theory it’s the right time to look at take-privates as valuations are dropping. But the execution risk is high, particularly in cases where the largest shareholder holds less than 10%,” said Chris Mogge, a partner at European buyout fund BC Partners.Other recent private equity swoops include a 1.6 billion pound ($1.97 billion) bid by a consortium of Astorg Asset Management and Epiris for Euromoney (ERM.L) which valued the FTSE 250-listed financial publisher at a 34% premium after four previous offers were rebuffed by its board. read more Also capturing the attention of private equity in recent weeks were power generating firm ContourGlobal (GLO.L), British waste-management specialist Biffa (BIFF.L) and bus and rail operator FirstGroup (FGP.L), with the latter rejecting the takeover approach. read more Trevor Green, head of UK equities at Aviva Investors (AV.L), said his team was stepping up engagement with company executives to thwart lowball bids, with unwelcome approaches from private equity made more likely in view of currency volatility.War in Europe, soaring energy prices and stagflation concerns have hit the euro and the British pound hard, with the former falling around 7% and the latter by 10% against the U.S. dollar this year.”We know this kind of currency movement encourages activity, and where there’s scope for a deal, shareholders will be rightly pushing for higher premiums to reflect that,” Green said.SUBDUED SPENDINGGlobally, private equity activity has eased after a record year in 2021, hit by raging inflation, recession fears and the rising cost of capital. Overall volumes fell 19% to $674 billion in the first half of the year, according to Dealogic data.Dealmaking across the board, including private equity deals, dropped 25.5% in the second quarter of this year from a year earlier to $1 trillion, according to Dealogic data. read more Buyout funds have played a major role in sustaining global M&A activity this year, generating transactions worth $405 billion in the second quarter.But as valuation disputes intensify, concerns sparked by rising costs of debt have prevented firms from pulling off deals for their preferred listed targets in recent months.Private equity firms including KKR, EQT and CVC Capital Partners ditched attempts to take control of German-listed laboratory supplier Stratec (SBSG.DE) in May due to price differences, three sources said. Stratec, which has a market value of 1.1 billion euros, has the Leistner family as its top shareholder with a 40.5% stake.EQT, KKR and CVC declined to comment. Stratec did not immediately return a request for comment.The risks of highly leveraged corporate takeovers have increased with financing becoming more expensive, leaving some buyers struggling to make the numbers on deals stack up, sources said.Meanwhile, piles of cash that private equity firms have raised to invest continue to grow, heaping pressure on partners to consider higher-risk deals structured with more expensive debt.”There is a risk premium for debt, which leads to higher deal costs,” said Marcus Brennecke, global co-head of private equity at EQT (EQT.N).The average yield on euro high yield bonds – typically used to finance leverage buyouts – has surged to 6.77% from 2.815% at the start of the year, according to ICE BofA’s index, and the rising cost of capital has slowed debt issuance sharply. (.MERHE00)As a result, private equity firms have increasingly relied on more expensive private lending funds to finance their deals, four sources said.But as share prices continue to slide, the gap between the premium buyers are willing to offer and sellers’ price expectations remains too wide for many and could take up to a year to narrow, two bankers told Reuters.In the UK, where Dealogic data shows a quarter of all European take-private deals have been struck this year, the average premium paid was 40%, in line with last year, according to data from Peel Hunt.”Getting these deals over the line is harder than it looks. The question really is going to be how much leverage (buyers can secure),” one senior European banker with several top private equity clients told Reuters.($1 = 0.8141 pounds)($1 = 0.9450 euros)Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comReporting by Joice Alves, Emma-Victoria Farr, Sinead Cruise, additional reporting by Yoruk Bahceli, editing by Pamela Barbaglia and Susan FentonOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. .

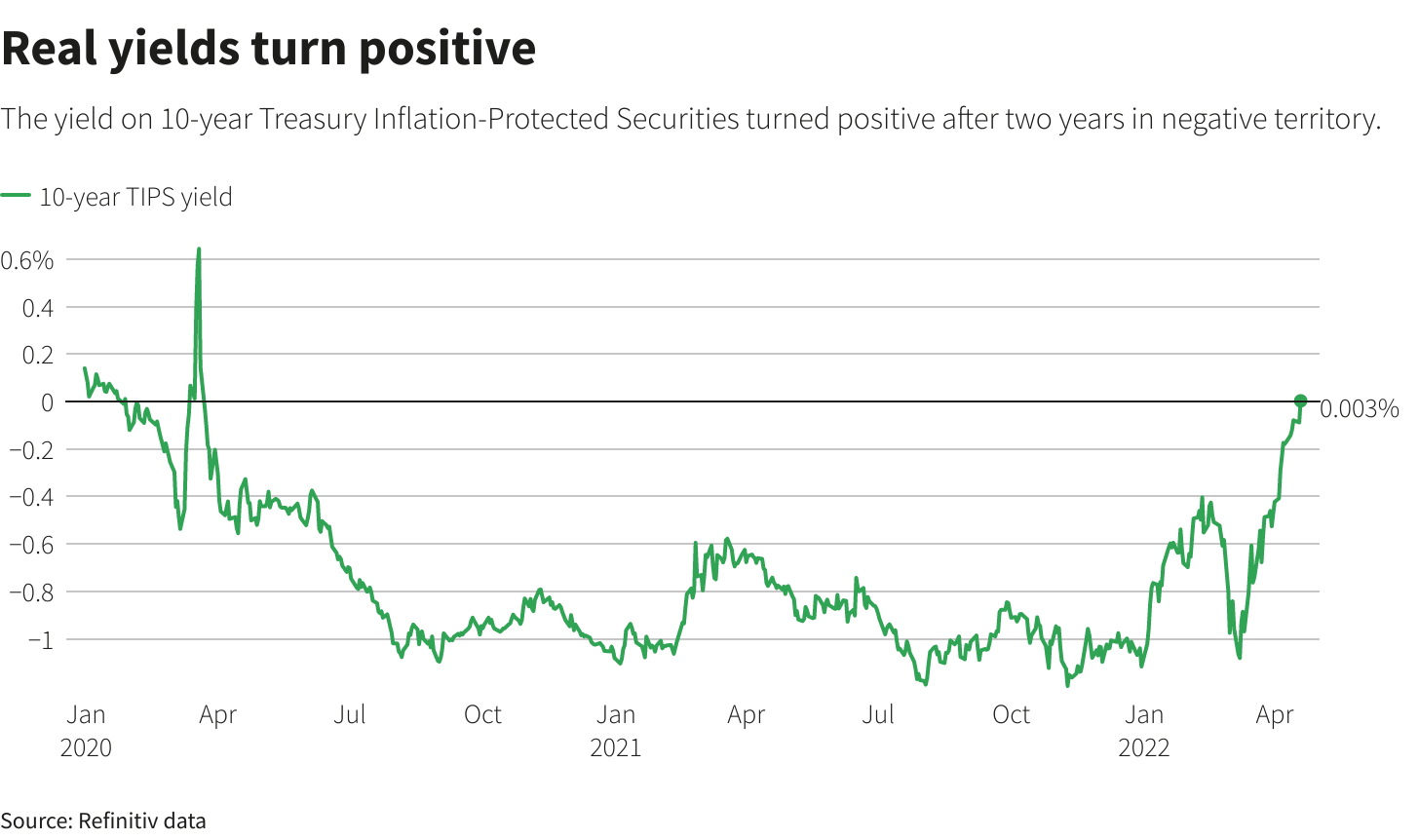

Analysis: Positive real yields may spell more trouble for U.S. stocks

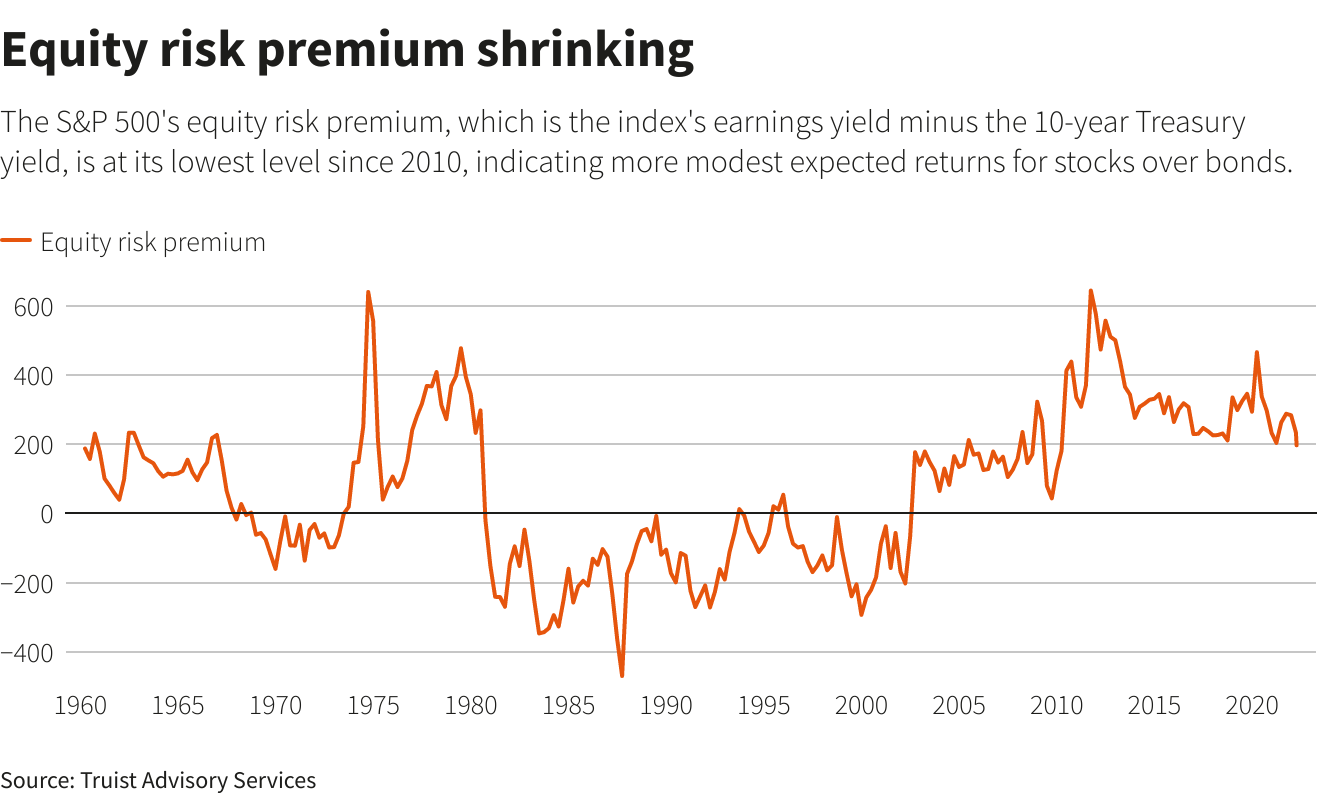

A street sign for Wall Street is seen in the financial district in New York, U.S., November 8, 2021. REUTERS/Brendan McDermid/File Photo/File PhotoRegister now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comNEW YORK, April 20 (Reuters) – A hawkish turn by the Federal Reserve is eroding a key support for U.S. stocks, as real yields climb into positive territory for the first time in two years.Yields on the 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) – also known as real yields because they subtract projected inflation from the nominal yield on Treasury securities – had been in negative territory since March 2020, when the Federal Reserve slashed interest rates to near zero. That changed on Tuesday, when real yields ticked above zero. Negative real yields have meant that an investor would have lost money on an annualized basis when buying a 10-year Treasury note, adjusted for inflation. That dynamic has helped divert money from U.S. government bonds and into a broad spectrum of comparatively riskier assets, including stocks, helping the S&P 500 (.SPX) more than double from its post-pandemic low.Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comAnticipation of tighter monetary policy, however, is pushing yields higher and may dent the luster of stocks in comparison to Treasuries, which are viewed as much less risky since they are backed by the U.S. government. Reuters GraphicsOn Tuesday, stocks shrugged off the rise in yields, with the S&P 500 ending up 1.6% on the day. Still, the S&P 500 is down 6.4% this year, while the yield on the 10-year TIPS has climbed more than 100 basis points.”Real 10-year yields are the risk-free alternative to owning stocks,” said Barry Bannister, chief equity strategist at Stifel. “As real yield rises, at the margin it makes stocks less attractive.”One key factor influenced by yields is the equity risk premium, which measures how much investors expect to be compensated for owning stocks over government bonds.Rising yields have helped result in the measure standing at its lowest level since 2010, Truist Advisory Services said in a note last week.

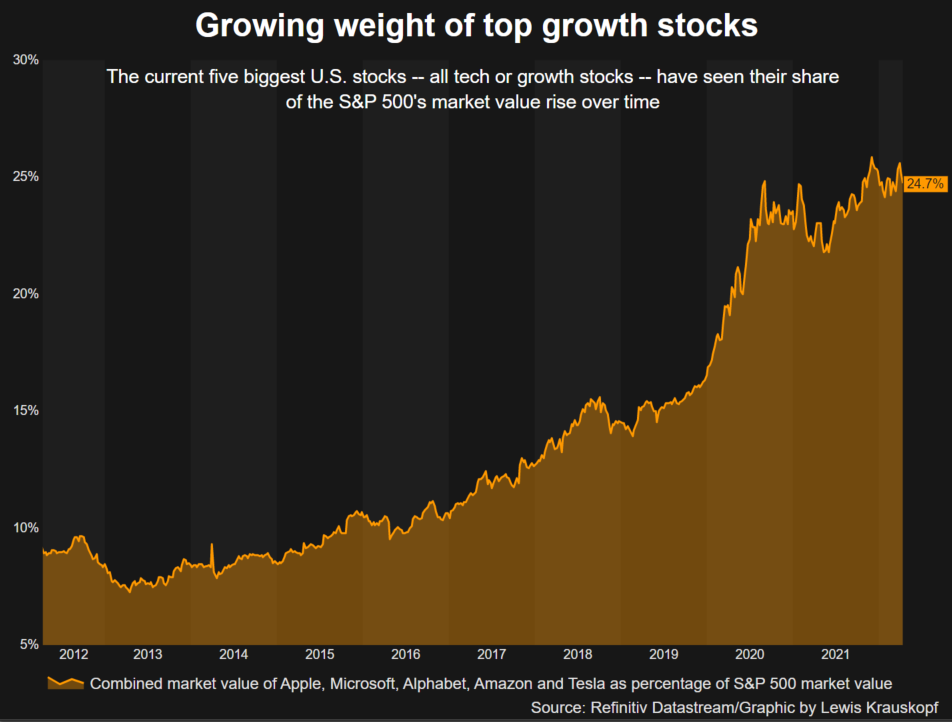

Reuters GraphicsOn Tuesday, stocks shrugged off the rise in yields, with the S&P 500 ending up 1.6% on the day. Still, the S&P 500 is down 6.4% this year, while the yield on the 10-year TIPS has climbed more than 100 basis points.”Real 10-year yields are the risk-free alternative to owning stocks,” said Barry Bannister, chief equity strategist at Stifel. “As real yield rises, at the margin it makes stocks less attractive.”One key factor influenced by yields is the equity risk premium, which measures how much investors expect to be compensated for owning stocks over government bonds.Rising yields have helped result in the measure standing at its lowest level since 2010, Truist Advisory Services said in a note last week. Reuters GraphicsHEADWIND TO GROWTH SHARESHigher yields in particular dull the allure of companies in technology and other high-growth sectors, with those companies’ cash flows often more weighted in the future and diminished when discounted at higher rates.That may be bad news for the broader market. The heavy presence of tech and other growth stocks in the S&P 500 means the index’s overall expected dividends are weighted in the future at close to their highest level ever, according to BofA Global Research. Five massive, high-growth stocks, for example, now make up 22% of the weight of the S&P 500.At the same time, growth shares in recent years have been highly linked to the movement of real yields.Since 2018, a ratio comparing the performance of the Russell 1000 growth index (.RLG) to its counterpart for value stocks (.RLV) – whose cash flows are more near-term – has had a negative 96% correlation with 10-year real rates, meaning they tend to move in opposite directions from growth stocks, according to Ohsung Kwon, a U.S. equity strategist at BofA Global Research.Rising yields are “a bigger headwind to equities than (they have) been in history,” he said.

Reuters GraphicsHEADWIND TO GROWTH SHARESHigher yields in particular dull the allure of companies in technology and other high-growth sectors, with those companies’ cash flows often more weighted in the future and diminished when discounted at higher rates.That may be bad news for the broader market. The heavy presence of tech and other growth stocks in the S&P 500 means the index’s overall expected dividends are weighted in the future at close to their highest level ever, according to BofA Global Research. Five massive, high-growth stocks, for example, now make up 22% of the weight of the S&P 500.At the same time, growth shares in recent years have been highly linked to the movement of real yields.Since 2018, a ratio comparing the performance of the Russell 1000 growth index (.RLG) to its counterpart for value stocks (.RLV) – whose cash flows are more near-term – has had a negative 96% correlation with 10-year real rates, meaning they tend to move in opposite directions from growth stocks, according to Ohsung Kwon, a U.S. equity strategist at BofA Global Research.Rising yields are “a bigger headwind to equities than (they have) been in history,” he said. Top five stocks market cap as percentage of S&P 500Bannister estimates the S&P 500 could retest its lows of the year, which included a drop in March of 13% from the index’s record high, should the yield on the 10-year TIPS rise to 0.75% and the earnings outlook – a key component of the risk premium – remain unchanged.Lofty valuations also make stocks vulnerable if yields continue rising. Though the tumble in stocks has moderated valuations this year, the S&P 500 still trades at about 19 times forward earnings estimates, compared with a long-term average of 15.5, according to Refinitiv Datastream.“Valuations aren’t great on stocks right now. That means that capital may look at other alternatives to stocks as they become more competitive,” said Matthew Miskin, co-chief investment strategist at John Hancock Investment Management.Still, some investors believe stocks can survive just fine with rising real yields, for now. Real yields were mostly in positive territory over the past decade and ranged as high as 1.17% while the S&P 500 has climbed over 200%.JPMorgan strategists earlier this month estimated that equities could cope with 200 basis points of real yield increases. They advised clients maintain a large equity versus bond overweight.”If bond yield rises continue, they could eventually become a problem for equities,” the bank’s strategists said. “But we believe current real bond yields at around zero are not high enough to materially challenge equities.”Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comReporting by Lewis Krauskopf in New York

Top five stocks market cap as percentage of S&P 500Bannister estimates the S&P 500 could retest its lows of the year, which included a drop in March of 13% from the index’s record high, should the yield on the 10-year TIPS rise to 0.75% and the earnings outlook – a key component of the risk premium – remain unchanged.Lofty valuations also make stocks vulnerable if yields continue rising. Though the tumble in stocks has moderated valuations this year, the S&P 500 still trades at about 19 times forward earnings estimates, compared with a long-term average of 15.5, according to Refinitiv Datastream.“Valuations aren’t great on stocks right now. That means that capital may look at other alternatives to stocks as they become more competitive,” said Matthew Miskin, co-chief investment strategist at John Hancock Investment Management.Still, some investors believe stocks can survive just fine with rising real yields, for now. Real yields were mostly in positive territory over the past decade and ranged as high as 1.17% while the S&P 500 has climbed over 200%.JPMorgan strategists earlier this month estimated that equities could cope with 200 basis points of real yield increases. They advised clients maintain a large equity versus bond overweight.”If bond yield rises continue, they could eventually become a problem for equities,” the bank’s strategists said. “But we believe current real bond yields at around zero are not high enough to materially challenge equities.”Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comReporting by Lewis Krauskopf in New York

Editing by Ira Iosebashvili and Matthew LewisOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. .

Column: Elusive bond risk premium misses its curtain call: Mike Dolan

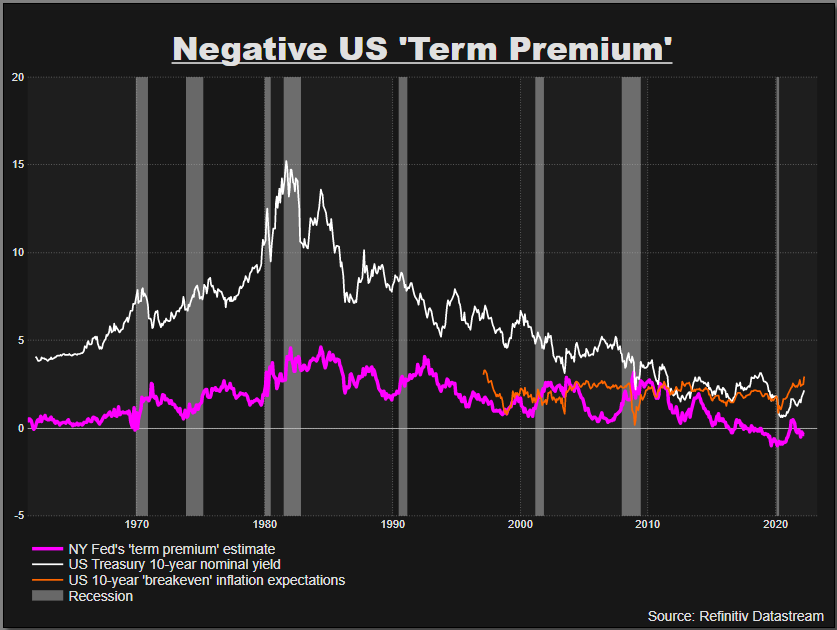

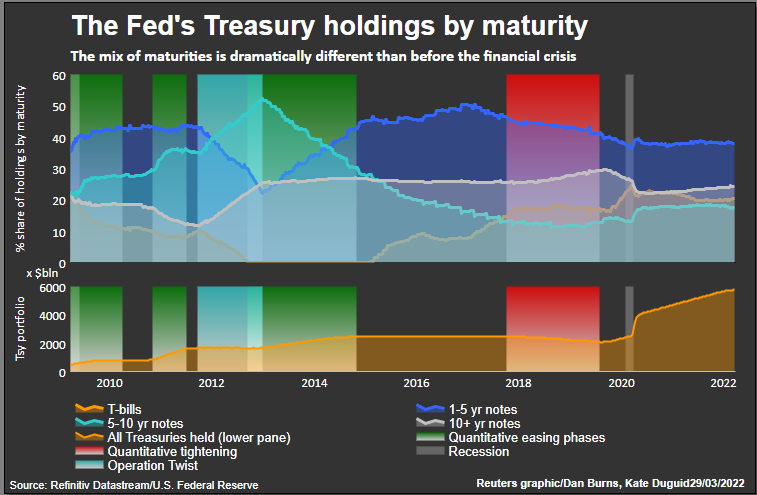

LONDON, March 30 (Reuters) – If not now, when? Investors typically demand some added compensation for holding a security over many years to cover all the unknowables over long horizons – making the absence of such a premium in bond markets right now seem slightly bizarre.Disappearance of the so-called “term premium” in 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds over the past 5 years has puzzled analysts and policymakers and been blamed variously on subdued inflation expectations or distortions related to central bank bond buying.And yet it’s rarely, if ever, been more difficult to fathom the decade ahead – at least in terms of inflation, interest rates or indeed quantitative easing or tightening.Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comInflation is running at a 40-year high after the pandemic forced wild swings in economic activity and supply bottlenecks and was then compounded by an energy price spike due to war in Ukraine that may redraw the geopolitical map.The U.S. Federal Reserve and other central banks are scrambling to normalise super easy monetary policies to cope – not really knowing whether to focus on reining in runaway prices or tackle what Bank of England chief Andrew Bailey this week described as a “historic shock” to real household incomes.Bond yields have surged, much like they did in the first quarter of last year. But this time bond funds have suffered one of their worst quarters in more than 20 years and some measures of Treasury price volatility are at their highest since banking crash of 2008. (.MOVE3M)But the most-followed estimates of term premia embedded in bond markets remain deeply negative. And this matters a lot to a whole host of critical bond market signals, not least the unfolding inversion of the U.S. Treasury curve between short and long-term yields that has presaged recessions in the past.”The 10-year term premium has barely budged even as inflation spiked to 8%, suggesting that long-dated yields are probably still capped by the Fed’s record-high balance sheet,” said Franklin Templeton’s fixed income chief Sonal Desai. “Or maybe investors think the Fed will blink and ease policy again once asset prices start a meaningful correction.””In either case, I think markets are still underestimating the magnitude of the monetary policy tightening ahead,” said Desai, adding that expectations of another more than 2 percentage points of Fed hikes this year still likely leaves real policy rates deeply negative by December even if inflation eases to 5%. US ‘term premium’ stays negative

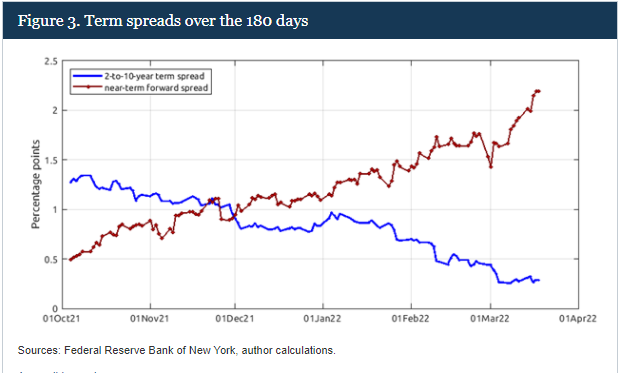

US ‘term premium’ stays negative Fed contrast between Yield Curve and Near Term Forward SpreadBUMP IN THE NIGHTSo what’s the beef with the term premium?In effect, the Treasury term premium is meant to measure the additional yield demanded by investors for buying and holding a 10-year bond to maturity as opposed to buying a one year bond and rolling it over for 10 years with a new coupon.In theory it covers all the things that might go bump in the night over a decade hence – including the outside chance of credit or even political risk – but it mostly reflects uncertainty about future Fed rates and inflation expectations.At zero, you’d assume investors are indifferent to holding the 10-year today as opposed to rolling 10 one-year notes.But the New York Fed’s measure of the 10-year term premium remains deeply negative to the tune of -32 basis points – ostensibly suggesting investors actually prefer holding the longer-duration asset.Although the premium popped back positive in the first half of last year, it’s been stuck around zero or below since 2017 – oddly in the face of the Fed’s last attempt to unwind its balance sheet.And the persistent and puzzling erosion of the term premium to zero and below brings it back to the 1960s, not the much-vaunted inflation-ravaged 1970s that everyone seems to think we’re back in.It matters a lot now as the debate about the inversion of the 2-10 yield curve heats up and many argue that the signal sent by that inversion is less clear about a coming recession as it’s distorted by the disappearance of the term premium.In the absence of a term premium, the long-term yield curve is just a reflection of long-run policy rate expectations that will inevitably see some retreat if the Fed is successful in taming inflation over the next two years.Fed Board economists Eric Engstrom and Steven Sharpe late last week also dismissed the market’s obsession with a 2-10 year yield inversion signalling recession.In a blog called ‘(Don’t Fear) The Yield Curve’ they said near term forward rate spreads out to 18 months were much more informative about the chance of a looming recession, just as accurate over time and – significantly – heading in the opposite direction right now.The main reason they pushed back on the 2-10s was it contained a whole host of information about the world beyond two years that’s simply less reliable as an economic signal and “buffeted by other significant factors such as risk premiums on long-term bonds.”But what could see the term premium return?Presumably the Fed’s planned balance sheet rundown, or quantitative tightening (QT), would be a prime candidate if indeed its long-term bond buying has distorted term premia.But the last Fed attempt at QT in 2017-19 didn’t do that and Morgan Stanley thinks it will be some time yet before just allowing short-term bonds on its balance sheet to roll off and mature gets replaced by outright sales of longer-term bonds.”QT is not the opposite of QE; asset sales are.”Of course, maybe the world just hasn’t changed that much – in terms of ageing demographics, excess savings and pension fund demand, falling potential growth and negative real interest rates. Once this current storm has passed, investors seem to think that will dominate once more. read more

Fed contrast between Yield Curve and Near Term Forward SpreadBUMP IN THE NIGHTSo what’s the beef with the term premium?In effect, the Treasury term premium is meant to measure the additional yield demanded by investors for buying and holding a 10-year bond to maturity as opposed to buying a one year bond and rolling it over for 10 years with a new coupon.In theory it covers all the things that might go bump in the night over a decade hence – including the outside chance of credit or even political risk – but it mostly reflects uncertainty about future Fed rates and inflation expectations.At zero, you’d assume investors are indifferent to holding the 10-year today as opposed to rolling 10 one-year notes.But the New York Fed’s measure of the 10-year term premium remains deeply negative to the tune of -32 basis points – ostensibly suggesting investors actually prefer holding the longer-duration asset.Although the premium popped back positive in the first half of last year, it’s been stuck around zero or below since 2017 – oddly in the face of the Fed’s last attempt to unwind its balance sheet.And the persistent and puzzling erosion of the term premium to zero and below brings it back to the 1960s, not the much-vaunted inflation-ravaged 1970s that everyone seems to think we’re back in.It matters a lot now as the debate about the inversion of the 2-10 yield curve heats up and many argue that the signal sent by that inversion is less clear about a coming recession as it’s distorted by the disappearance of the term premium.In the absence of a term premium, the long-term yield curve is just a reflection of long-run policy rate expectations that will inevitably see some retreat if the Fed is successful in taming inflation over the next two years.Fed Board economists Eric Engstrom and Steven Sharpe late last week also dismissed the market’s obsession with a 2-10 year yield inversion signalling recession.In a blog called ‘(Don’t Fear) The Yield Curve’ they said near term forward rate spreads out to 18 months were much more informative about the chance of a looming recession, just as accurate over time and – significantly – heading in the opposite direction right now.The main reason they pushed back on the 2-10s was it contained a whole host of information about the world beyond two years that’s simply less reliable as an economic signal and “buffeted by other significant factors such as risk premiums on long-term bonds.”But what could see the term premium return?Presumably the Fed’s planned balance sheet rundown, or quantitative tightening (QT), would be a prime candidate if indeed its long-term bond buying has distorted term premia.But the last Fed attempt at QT in 2017-19 didn’t do that and Morgan Stanley thinks it will be some time yet before just allowing short-term bonds on its balance sheet to roll off and mature gets replaced by outright sales of longer-term bonds.”QT is not the opposite of QE; asset sales are.”Of course, maybe the world just hasn’t changed that much – in terms of ageing demographics, excess savings and pension fund demand, falling potential growth and negative real interest rates. Once this current storm has passed, investors seem to think that will dominate once more. read more  Fed balance sheet and maturitiesThe author is editor-at-large for finance and markets at Reuters News. Any views expressed here are his ownRegister now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comby Mike Dolan, Twitter: @reutersMikeD. Editing by Jane MerrimanOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.Opinions expressed are those of the author. They do not reflect the views of Reuters News, which, under the Trust Principles, is committed to integrity, independence, and freedom from bias. .

Fed balance sheet and maturitiesThe author is editor-at-large for finance and markets at Reuters News. Any views expressed here are his ownRegister now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comby Mike Dolan, Twitter: @reutersMikeD. Editing by Jane MerrimanOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.Opinions expressed are those of the author. They do not reflect the views of Reuters News, which, under the Trust Principles, is committed to integrity, independence, and freedom from bias. .

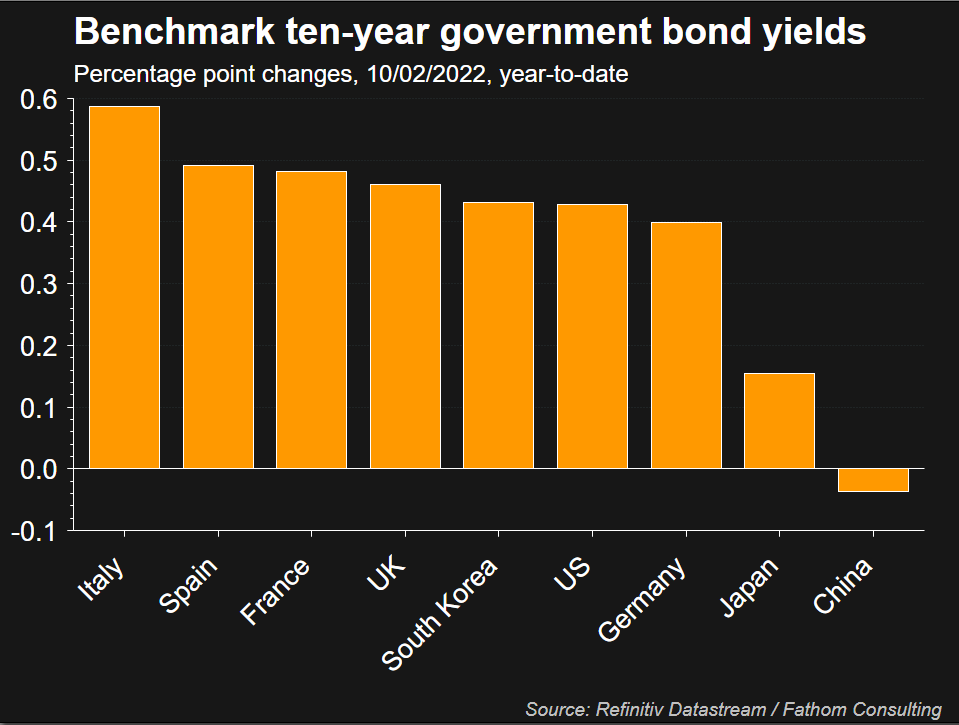

Analysis: Where now after 2% yield? Bond investors take stock

The Federal Reserve building is seen in Washington, U.S., January 26, 2022. REUTERS/Joshua Roberts/File PhotoRegister now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comRegisterNEW YORK, Feb 10 (Reuters) – U.S. Treasury yields have shot higher this year, rising faster than many forecast. Investors are now assessing if anticipation of a more hawkish Fed will continue to push levels up, with the potential to upset riskier assets.Expectations that the U.S. Federal Reserve may increase rates more aggressively than anticipated to counter rising inflation have pushed up yields while flattening the U.S. Treasury yield curve. That matters as bond yields impact global asset prices as well as consumer loans and mortgages. The shape of the U.S. Treasury yield curve can also help predict how the economy will fare.On Thursday, yields on 10-year notes hit 2% after higher-than-anticipated inflation data. Federal funds rate futures showed an increased chance of a half percentage-point tightening at next month’s meeting after the data, while strategists said the data increased the chances of swifter moves to reduce the Fed’s balance sheet. The central bank’s nearly $9 trillion portfolio doubled in size during the pandemic. read more Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comRegister“The market is starting to price in a much more aggressive path of rate hikes … clearly there is a sense of urgency again”, said Subadra Rajappa, head of U.S. rates strategy at Societe Generale.Yields, which move inversely to prices, are up from 1.79% at the beginning of February. The last time they breached 2% was August 2019.”I would say the chances of yields continuing to go higher are pretty high,” said Gargi Chaudhuri, Head of iShares Investment Strategy, Americas, at BlackRock, speaking ahead of the data.FOREIGN COMPETITIONCompetition in other markets for yield may be sapping demand for Treasuries and helping push yields higher, Chaudhuri said.A second rate hike by the Bank of England last week, and expectations of faster policy tightening by the European Central Bank (ECB), added to U.S. bonds’ weakness, with borrowing costs in Europe – as well as Japanese government bond yields – having jumped to multi-year highs in recent days. read more “Investors have these other markets to gravitate towards that they didn’t in the past, and that will require investors that are focusing on U.S. markets to seek a higher term premium and therefore will impact yields higher,” Chaudhuri said.Japan’s benchmark 10-year government bond yield is around its highest level since January 2016 at 0.220% while Germany’s 10-year government bond yield , at 0.255%, is at its highest since January 2019. read more  FEDFor Kelsey Berro, fixed income portfolio manager at J.P. Morgan Asset Management, the level of yields in overseas markets such as Japan or Germany have made U.S. rates comparably more attractive, preventing a sustainable sell off, but that is expected to change.”Already you should start to see that some of these foreign investors take a second look at their home countries rather than reaching for yields in the U.S.,” she said.Still, there was strong demand seen for a recent 10-year Treasury auction, although it was unclear how much overseas bidders participated. SPEEDY ASCENTThe rise in US yields has come faster than many anticipated: In December, a Reuters poll forecast that 10-year note yields would rise to around 2% towards the end of 2022 – a level it has reached in the first couple of months. read more Some banks have been updating that view. Goldman Sachs analysts on Wednesday raised their forecast for the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield to 2.25% by end-2022, from a previous year-end target of 2%.The pace of gains has caused volatility in other assets. U.S. equities have been rocky this year, with shares of tech companies particularly volatile, as expectations of higher yields threaten to erode the value of their future earnings.Gene Podkaminer, Head of Research for Franklin Templeton Investment Solutions, called 2% on the benchmark 10-year a “psychological” level that could make U.S. government bonds more attractive versus other assets, such as volatile stocks.”When you start getting close to 2% … all of a sudden Treasuries are looking more appealing,” Podkaminer said earlier this week.One commonly cited metric still favors stocks, however.The equity risk premium – or the extra return investors receive for holding stocks over risk-free government bonds – favors equities over the next year, Keith Lerner, co-chief investment officer at Truist Advisory Services, said on Wednesday.The S&P 500 has historically beaten the one-year return for the 10-year Treasury note by an average of 11.8% when the premium stood at Wednesday’s level of 260 points, Lerner said.“I don’t think the U.S. 10-year yield hitting 2% would have a big impact on the stock markets per se,” said Manish Kabra, head of U.S. equity strategy at Societe Generale, citing the equity risk premium.However, “we could see some pressure if yields go to 2.5%,” she said.Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comRegisterReporting by Davide Barbuscia; additional reporting by Saikat Chatterjee in London and Lewis Krauskopf in New York; editing by Ira Iosebashvili and Megan DaviesOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. .

FEDFor Kelsey Berro, fixed income portfolio manager at J.P. Morgan Asset Management, the level of yields in overseas markets such as Japan or Germany have made U.S. rates comparably more attractive, preventing a sustainable sell off, but that is expected to change.”Already you should start to see that some of these foreign investors take a second look at their home countries rather than reaching for yields in the U.S.,” she said.Still, there was strong demand seen for a recent 10-year Treasury auction, although it was unclear how much overseas bidders participated. SPEEDY ASCENTThe rise in US yields has come faster than many anticipated: In December, a Reuters poll forecast that 10-year note yields would rise to around 2% towards the end of 2022 – a level it has reached in the first couple of months. read more Some banks have been updating that view. Goldman Sachs analysts on Wednesday raised their forecast for the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield to 2.25% by end-2022, from a previous year-end target of 2%.The pace of gains has caused volatility in other assets. U.S. equities have been rocky this year, with shares of tech companies particularly volatile, as expectations of higher yields threaten to erode the value of their future earnings.Gene Podkaminer, Head of Research for Franklin Templeton Investment Solutions, called 2% on the benchmark 10-year a “psychological” level that could make U.S. government bonds more attractive versus other assets, such as volatile stocks.”When you start getting close to 2% … all of a sudden Treasuries are looking more appealing,” Podkaminer said earlier this week.One commonly cited metric still favors stocks, however.The equity risk premium – or the extra return investors receive for holding stocks over risk-free government bonds – favors equities over the next year, Keith Lerner, co-chief investment officer at Truist Advisory Services, said on Wednesday.The S&P 500 has historically beaten the one-year return for the 10-year Treasury note by an average of 11.8% when the premium stood at Wednesday’s level of 260 points, Lerner said.“I don’t think the U.S. 10-year yield hitting 2% would have a big impact on the stock markets per se,” said Manish Kabra, head of U.S. equity strategy at Societe Generale, citing the equity risk premium.However, “we could see some pressure if yields go to 2.5%,” she said.Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comRegisterReporting by Davide Barbuscia; additional reporting by Saikat Chatterjee in London and Lewis Krauskopf in New York; editing by Ira Iosebashvili and Megan DaviesOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. .